TextMINING

Estelle BlaschkeThe history of photography has always been connected to the industrial history of exploiting raw materials—the chemical substances silver bromide, nitrate, or acetate for the analogue process or the semiconductor silicon as an essential component of digital photography. However, mining also refers to the harvesting and exploitation of images themselves, meaning the image content produced and the data recorded when taking a photograph.

MINING

The history of photography has always been connected to the industrial history of exploiting raw materials—the chemical substances silver bromide, nitrate, or acetate for the analogue process or the semiconductor silicon as an essential component of digital photography. However, mining also refers to the harvesting and exploitation of images themselves, meaning the image content produced and the data recorded when taking a photograph.

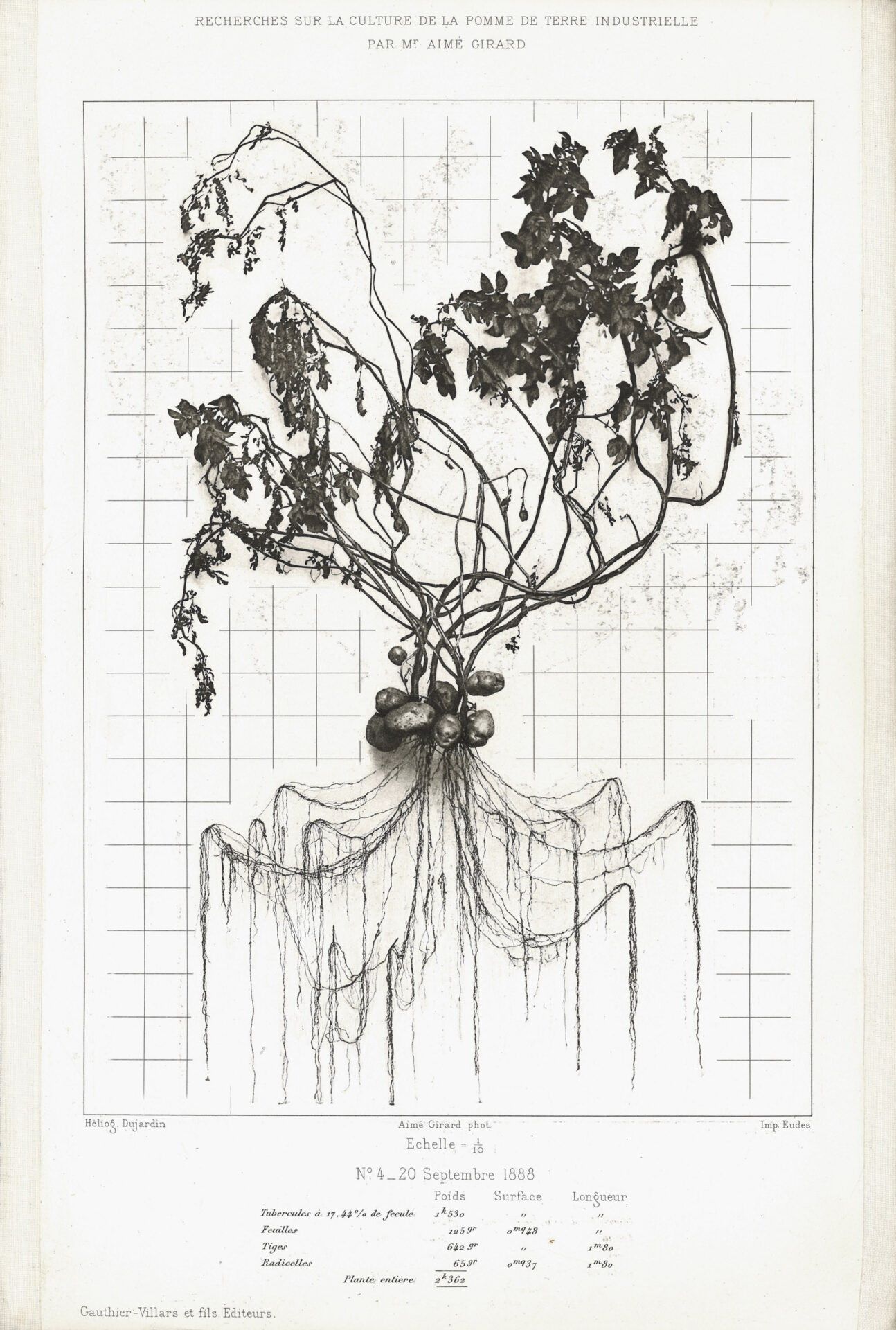

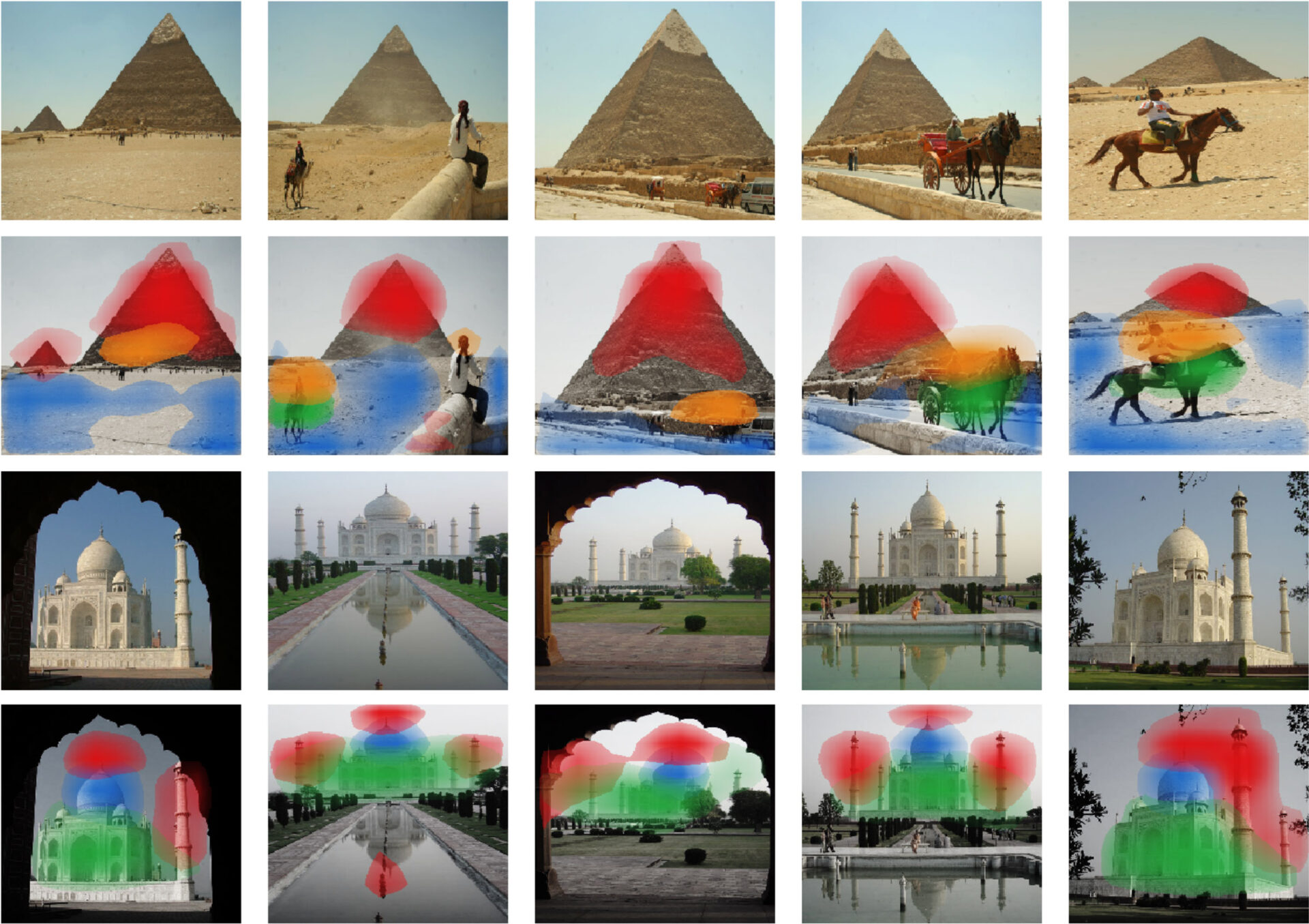

The limitless production, usually attributed to the banalization of photography, is of particular importance with regard to the contemporary mining technologies that are so pervasive in computing. Here, quantity is not a deficiency but a distinct quality of the medium. Easily available and produced at very little cost, image datasets are the basic raw material for image computing. When organized, classified, and annotated in image databases such as ImageNet, the Open Images database, or the proprietary datasets of the Big Five (Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft), the masses of indexed images allow for the development of image-recognition software. So-called computer vision—the automatic identification of objects and patterns in images—refers back to the long-held dream of organizing images according to their iconographic similarities. It also echoes the cybernetic imaginary of machine-assisted visual literacy.

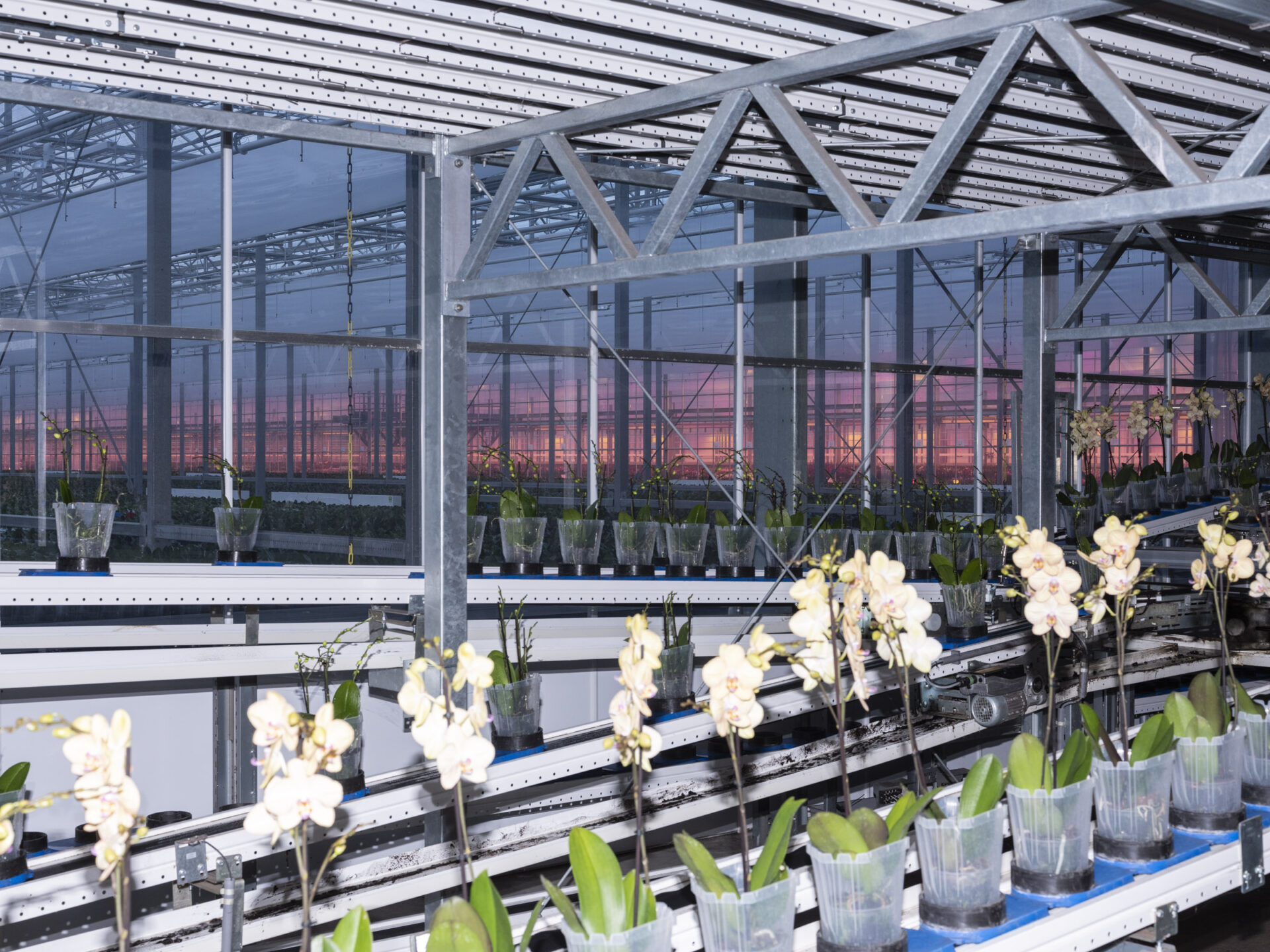

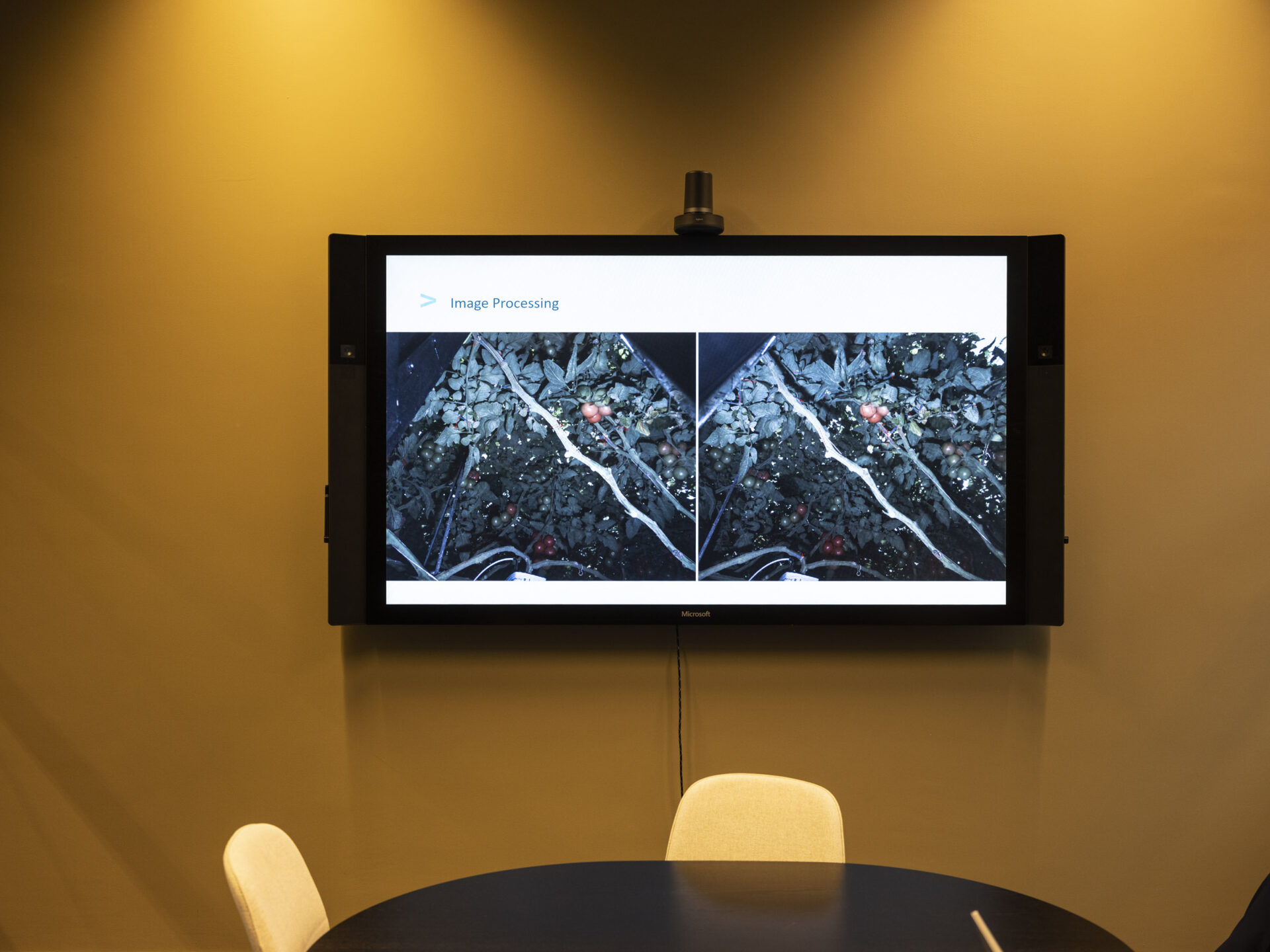

Today, computer vision has become widespread in data-driven engineering, manufacturing, and industrial agriculture as part of robotics and the continuous automation of production processes. The ultimate goal is machine-to-machine communication that largely operates without human direction. In addition, photographs are continuously created to monitor and optimize every aspect of the production process. Such photographs are operational in nature. They are deeply embedded in the production process and shaping it at the same time. While these technologies are still far from constituting a scalable practice—human labor, after all, especially in agriculture, is still more accurate, flexible, and cheap—they represent an additional function of contemporary photography: that is, photography as a catalyst for machine learning.

Machine learning, in turn, feeds back into the aesthetics, appearances, and visual culture of photography itself. It is present in the filter technologies in smart phones, in algorithms that structure search results and help navigate the abundance of simultaneously unfettered and networked images, as well as in computational photographs that are entirely artificial.

Die Geschichte der Fotografie ist seit jeher mit der Geschichte der industriellen Ausbeutung von Rohstoffen verbunden: chemische Substanzen wie Silberbromid, -nitrat oder -acetat für das analoge Verfahren oder Silizium in Halbleitern, ein wesentlicher Bestandteil der digitalen Fotografie. Der Begriff „Mining“ bezieht sich jedoch auch auf das massenhafte Sammeln und Verwerten von Bildern selbst, beziehungsweise auf die bei der Aufnahme einer Fotografie erzeugten Bildinhalte und aufgezeichneten Daten.

Die grenzenlose Produktion, die üblicherweise auf die Banalisierung der Fotografie zurückgeführt wird, ist für die heutigen, in der Informatik so allgegenwärtigen Mining-Technologien von besonderer Bedeutung. Hier ist die Quantität kein Makel, sondern ein Qualitätsmerkmal des Mediums. Leicht verfügbare und kostengünstig zusammengestellte Bilddatensätze sind das grundlegende Rohmaterial für die Bildverarbeitung. In Bilddatenbanken wie ImageNet, der Open Images Database oder den proprietären Datensätzen der Big Five (Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Google und Microsoft) organisiert, klassifiziert und mit Metadaten angereichert, ermöglichen die Massen an indexierten Bildern die Entwicklung von Bilderkennungssoftware. Die sogenannte Computer Vision, die automatische Identifizierung von Objekten und Mustern, geht auf den lang gehegten Traum zurück, Bilder nach ihrer ikonografischen Ähnlichkeit zu betrachten und zu ordnen. Auch gründet sie in der kybernetischen Idee von maschinengestützter visueller Kompetenz.

Heute ist die Computer Vision im datengesteuerten Ingenieurwesen, in der Fertigungstechnik und der industriellen Landwirtschaft als Teil der Robotik und der kontinuierlichen Automatisierung von Produktionsprozessen weit verbreitet. Das Ziel ist es, eine direkte Kommunikation zwischen Maschinen herzustellen, die weitestgehend ohne menschliche Anleitung funktioniert. In diesen Produktionsprozessen werden kontinuierlich Fotografien erstellt, um jeden Aspekt des Produktionsablaufs zu überwachen und zu optimieren. Die hergestellten Fotografien sind operativer Natur. Sie sind fest in den Produktionsvorgang eingebettet und prägen ihn gleichzeitig. Während diese Technologien noch weit von einer breiten Anwendung entfernt sind – menschliche Arbeit, insbesondere in der Landwirtschaft, ist immer noch genauer, flexibler und meist billiger –, repräsentieren sie eine zusätzliche Funktion der zeitgenössischen Fotografie: der Fotografie als Katalysator für maschinelles Lernen.

Dabei fließt das maschinelle Lernen wiederum in die Ästhetik, das Erscheinungsbild und die visuelle Kultur der Fotografie selbst ein. Es beeinflusst nicht nur die Filtertechnologien von Smartphones und findet sich in computergenerierten Bildern wieder, die Fotografien imitieren sollen, sondern es kommt in den Algorithmen zum Einsatz, die Suchergebnisse strukturieren und uns dabei helfen, durch die Fülle der entfesselten und zugleich miteinander vernetzten Bilder zu navigieren.

La storia della fotografia è sempre stata legata alla storia industriale dello sfruttamento delle materie prime; dall’argento (bromuro, nitrato, acetato) del processo analogico si è passati al silicio, semiconduttore e componente essenziale per la fotografia digitale. Il termine estrazione (mining), in ogni caso, si riferisce anche al processo di raccolta e sfruttamento delle immagini stesse, nel senso del contenuto che si produce e dei dati che vengono registrati ogni volta che si realizza una fotografia.

La produzione senza limiti, che viene in genere attribuita alla banalizzazione della fotografia, è particolarmente importante quando si pensa alle tecnologie di estrazione e lettura dei dati che sono tanto diffuse nei processi di analisi digitale (computing). In questo caso, la quantità non è un difetto, ma una qualità distintiva del medium. Set di immagini preesistenti, facilmente acquisibili e prodotti a basso costo, sono il materiale di base per l’analisi delle nuove immagini. Una volta organizzate, classificate e annotate in banche dati come ImageNet, il database Open Images o i dataset proprietari dei Big Five (Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Google, Microsoft), le masse di immagini indicizzate consentono lo sviluppo di software per il riconoscimento. La cosiddetta “computer vision” – l’identificazione automatica di oggetti e modelli nelle immagini – riconduce al vecchio e ricorrente sogno di organizzare le immagini sulla base delle loro somiglianze iconografiche, rimandando anche all’immaginario cibernetico delle tecnologie di assistenza robotizzata della letteratura.

Oggi la computer vision si è diffusa largamente nei campi dell’ingegneria, dell’industria manifatturiera e dell’agraria come parte della robotica e della progressiva automazione dei processi di produzione. L’obiettivo finale è il raggiungimento di un modello di comunicazione tra-macchina-e-macchina che operi ad ampio raggio senza il bisogno di direzione umana. Al fine di monitorare e ottimizzare ogni aspetto del processo di produzione, viene costantemente realizzata una grande quantità di immagini. In questo modo, le fotografie diventano immagini operative. Se queste tecnologie sono ancora lontane dal poter essere applicate su una scala più minuta – il lavoro dell’uomo, soprattutto in agricoltura, è ancora più accurato, flessibile ed economico – rappresentano comunque una funzione ulteriore della fotografia contemporanea: la fotografia come fattore fondamentale per l’apprendimento automatico (machine learning).

L’apprendimento automatico si nutre e viene influenzato dall’estetica, dalle apparenze e dalla cultura visiva della fotografia stessa. È presente nei filtri che gli smartphone applicano alle immagini, negli algoritmi che ordinano i risultati delle nostre ricerche e ci aiutano a navigare tra un’infinità di immagini contemporaneamente libere e interconnesse, e nella “fotografia computazionale”, che è interamente artificiale.

La photographie entretient une relation privilégiée avec l’extraction capitaliste des ressources. Par exemple, l’histoire de la photographie est une histoire continue d’exploitation des matières premières nécessaires au développement de substances chimiques, telles que le bromure, le nitrate ou l’acétate d’argent pour le processus analogique, ou le silicium en tant que semi-conducteur et composant essentiel de la photographie numérique. Cependant, le terme exploitation (en anglais mining) fait également référence à la collecte et à l’exploitation des images elles-mêmes, c’est-à-dire à l’extraction du contenu de l’image produite et des données enregistrées lors de la réalisation d’une photographie.

La production illimitée, que l’on attribue généralement à la banalisation de la photographie, revêt une importance particulière en ce qui concerne les technologies d’extraction qui sont si omniprésentes dans l’informatique d’aujourd’hui. Ici, la quantité n’est pas un défaut. C’est une qualité distincte du support. Les ensembles de données d’images, facilement disponibles et produits à très faible coût, constituent la matière première de base pour le traitement des images. Une fois organisées, classées et annotées dans des bases de données d’images telles que ImageNet, la base de données Open Images ou les ensembles de données propriétaires des Big Five (Apple, Amazon, Facebook/Meta, Google, Microsoft), les masses d’images indexées permettent le développement de logiciels de reconnaissance d’images. L’identification automatique d’objets et de motifs dans les images, connue sous le nom de “vision par ordinateur”, renvoie au vieux rêve de l’organisation des images en fonction de leurs similitudes iconographiques. Il fait également écho à l’imaginaire cybernétique d’une lecture visuelle assistée par machine, c’est-à-dire la possibilité d’interpréter automatiquement le contenu d’une image.

Aujourd’hui, la vision par ordinateur s’est généralisée dans l’ingénierie, la fabrication, l’architecture et l’agriculture industrielle fondées sur les données, dans le cadre de la robotique et de l’automatisation continue des processus de production. L’objectif ultime est une communication de machine à machine qui fonctionnerait en grande partie sans l’aide de l’homme. En outre, des photographies sont créées en permanence pour contrôler et optimiser chaque aspect du processus de production. Il s’agit donc d’images opérationnelles. Bien que ces technologies soient encore loin d’être une pratique évolutive – après tout, le travail humain, en particulier dans l’agriculture, est toujours plus précis, plus flexible et moins cher – elles représentent une fonction supplémentaire de la photographie contemporaine : La photographie en tant que catalyseur de l’apprentissage automatique.

L’apprentissage automatique, à son tour, alimente l’esthétique, les apparences et la culture visuelle de la photographie elle-même. Il est présent dans les technologies de filtrage des smartphones, dans les algorithmes qui structurent les résultats de recherche et aident à naviguer dans l’abondance d’images à la fois libres et en réseau. En outre, les photographies numériques et les données qu’elles produisent contribuent au développement d’images générées par ordinateur, y compris, plus récemment, l’intelligence artificielle générative, qui produit des images entièrement artificielles, mais qui imitent le photoréalisme.