TextCURRENCY

Estelle BlaschkePhotography is a product and a catalyst of the Industrial Age. From its beginnings, it became part of an economic system determined by supply and demand, circulation and investment. The medium documented the rapid growth of industrial societies. Photographs showcased material possessions of the nascent consumer culture and recorded the development of new transport systems, such as the road and rail networks, or the piling up of goods in warehouses destined for global trade. What is highlighted in many of the early tributes to the new medium is the ease, speed and efficiency with which a picture could be produced. Besides the material costs, – female and child labor, that was very distinct to the production process in photography, was very cheap – which, in turn, lay the ground for the distribution of affordable cameras and the proliferation of images.

CURRENCY

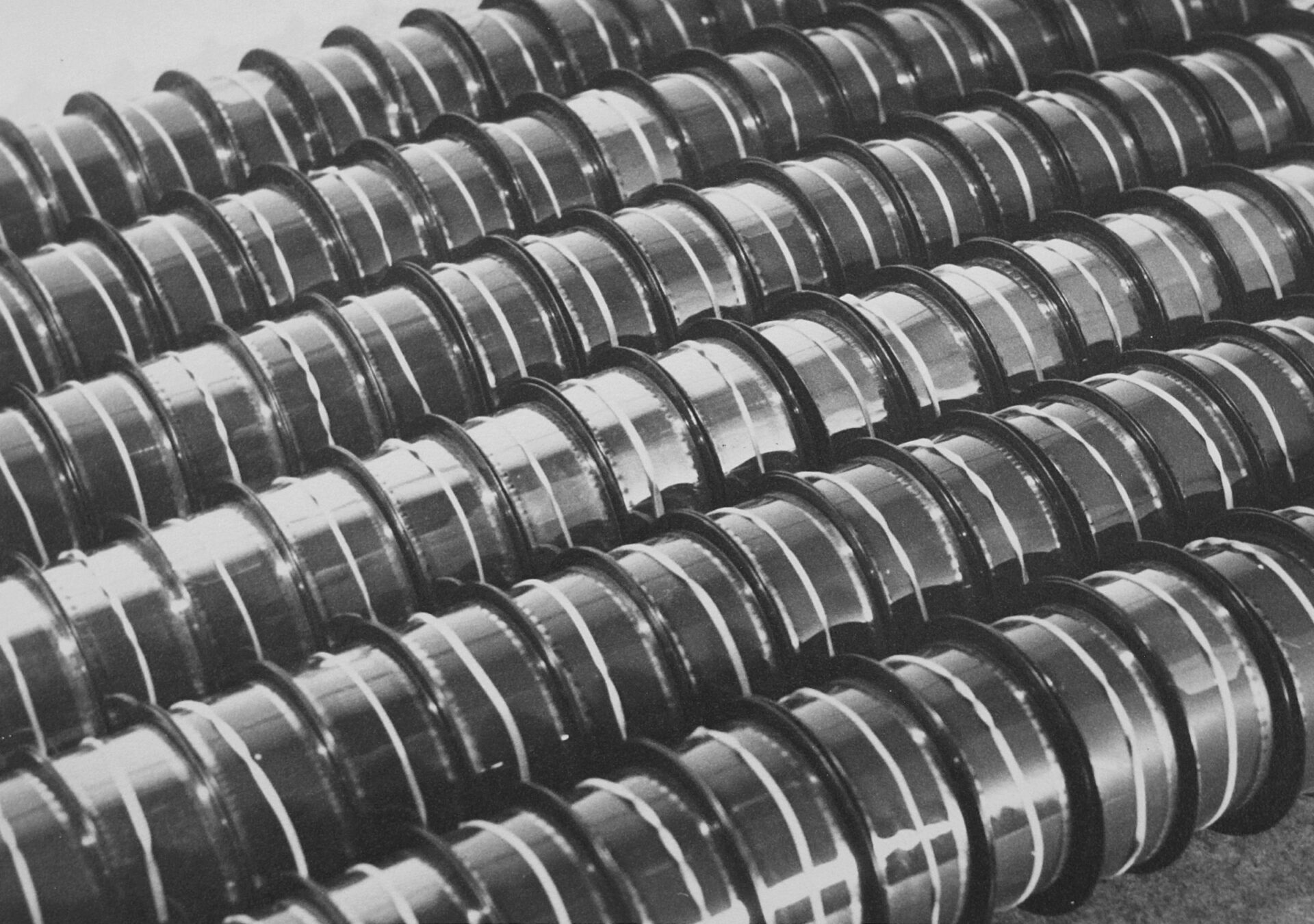

Photography is a product and a catalyst of the Industrial Age. From its beginnings, it became part of an economic system determined by supply and demand, circulation and investment. The medium documented the rapid growth of industrial societies. Photographs showcased material possessions of the nascent consumer culture and recorded the development of new transport systems, such as the road and rail networks, or the piling up of goods in warehouses destined for global trade. What is highlighted in many of the early tributes to the new medium is the ease, speed and efficiency with which a picture could be produced. Besides the material costs, – female and child labor, that was very distinct to the production process in photography, was very cheap – which, in turn, lay the ground for the distribution of affordable cameras and the proliferation of images.

Also, since its early days, photography was compared metaphorically to a form of currency. Already in the late 1850s, Oliver Wendell Holmes drew parallels between photography and the dual character of banknotes as virtual and material entities. Photographs were used as substitutes for the objects they depicted and referred to value systems located outside the image. The field in which this became central was advertising which expanded through photography, infiltrating private and public spaces alike.

What makes photographs particularly versatile resources is their reproducibility: they can easily be used, recycled and appear in different forms, places and contexts. However, outside the artistic realm, photographs are not valuable per se. Value is being created through the work that is put into the image and the services and infrastructures that surround it, such as by defining selection criteria, adding qualitative metadata to images or organizing them in databases. Also, the continued use and circulation are vital factors in the creation of value. The link between the systematic organization of visual information and the idea of currency is mirrored in terms such as image banks, stock photography and image mining.

With digital photography, value systems associated with the medium have shifted. While the market for press images and stock photography has been in continuous decline since the 2000s, image data and metadata have become a new commodity in data capitalism, in which images are exploited for a variety of purposes: to influence search results, to customize advertising, to contribute to scientific research, or as a surveillance tool. Social media services, in particular, have little interest in the images that accumulate on their servers, except for training image-recognition algorithms. However, they do have a vested interest in monetizing the data they collect through the vast amounts of uploaded visual material. The data generated by an image, one may conclude, has become as valuable as the image itself.

Die Fotografie ist ein Produkt und ein Katalysator des Industriezeitalters. Seit ihren Anfängen ist sie Teil eines Wirtschaftssystems, das von Angebot und Nachfrage, Zirkulation und Investition bestimmt wird. Das Medium dokumentierte das rasante Wachstum der Industriegesellschaften. Fotografien zeigten die materiellen Güter der aufkommenden Konsumkultur und dokumentierten die Entwicklung neuer Verkehrssysteme wie das Straßen- und Schienennetz oder die Anhäufung von Waren in Lagerhäusern, die für den globalen Handel bestimmt waren. In vielen der frühen Hommagen an das neue Medium wird die Leichtigkeit, Schnelligkeit und Effizienz hervorgehoben, mit der ein Bild produziert werden konnte. Neben den Materialkosten waren auch die Arbeitskräfte billig (die Fotoindustrie setzte auf die Arbeit von Frauen und Kindern), was wiederum die Grundlage für die Verbreitung erschwinglicher Kameras und die Zirkulation von Bildern war.

Darüber hinaus wurde die Fotografie von ihren Anfängen an metaphorisch mit einer Art Währung verglichen. Bereits in den späten 1850er Jahren zog Oliver Wendell Holmes Parallelen zwischen der Fotografie und dem Doppelcharakter von Banknoten als virtuelle und materielle Werte. Fotografien wurden als Ersatz für die abgebildeten Objekte verwendet und verwiesen auf Wertesysteme, die außerhalb des Bildes lagen. Der entscheidende Bereich, in dem dies zum Tragen kam, war die Werbung, die durch die Fotografie aufblühte und sowohl in den privaten als auch in den öffentlichen Raum eindrang.

Was Fotografien zu besonders vielseitigen Rohstoffen macht, ist ihre Reproduzierbarkeit: Sie sind flexibel einsetzbar und recycelbar und können in ganz verschiedenen Formen, Orten und Kontexten in Erscheinung treten. Außerhalb des künstlerischen Bereichs sind Fotografien jedoch nicht per se wertvoll. Wertigkeit entsteht durch die Arbeit, die in das Bild einfließt, sowie durch die Dienstleistungen und Infrastrukturen, welche es umgeben, etwa durch die Festlegung von Auswahlkriterien, das Hinzufügen von qualitativen Metadaten oder ihrer Organisation in Datenbanken. Auch die fortgesetzte Nutzung und Verbreitung sind entscheidende Faktoren für die Wertschöpfung. Die Verbindung zwischen der systematischen Organisation visueller Informationen und der Idee der Währung spiegelt sich nicht zuletzt in Begriffen wie Bildbanken, stock photography bzw. Vorratsfotografie und data mining wider.

Mit der digitalen Fotografie haben sich die mit dem Medium verbundenen und etablierte Wertesysteme verschoben. Während der Markt für Pressebilder und stock photography seit den 2000er Jahren kontinuierlich schrumpft, sind Bilddaten und Metadaten zu einer neuen Ware im Datenkapitalismus geworden, in dem Bilddaten für eine Vielzahl von Zwecken nutzbar gemacht und ausgewertet werden: zur Beeinflussung von Suchergebnissen, zur Personalisierung von Werbung, als Beitrag zur wissenschaftlichen Forschung oder als Überwachungsinstrument. Die Anbieter von Social Media, etwa, haben wenig Interesse an dem, was auf Bildern, die sich auf ihren Servern ansammeln, tatsächlich zu sehen ist. Die Bilder dienen ihnen in erster Linie als Trainingsmaterial für die Entwicklung von Bilderkennungsalgorithmen. Ein großes Interesse seitens dieser Unternehmen besteht jedoch an den Daten, welche sie durch die riesigen Mengen an hochgeladenem Bildmaterial sammeln und verkaufen. Die von einem Bild generierten Daten sind genauso wertvoll geworden wie das Bild selbst.

La fotografia è un prodotto e un catalizzatore dell’era industriale. Fin dal principio è diventata parte integrante di un sistema economico determinato da domanda e offerta, circolazione e investimento. Ha documentato la rapida crescita delle società industriali. Le fotografie hanno mostrato i beni materiali della nascente cultura del consumo e hanno registrato lo sviluppo di nuovi sistemi di trasporto, che comprendevano reti stradali e ferroviarie, e di magazzini in cui stoccare merci destinate al commercio globale. Ciò che emerge da molti dei primi tributi al nuovo medium è la facilità, la velocità e l’efficienza con cui si poteva produrre un’immagine, oltre all’accessibilità dei costi (il lavoro femminile e minorile, particolarmente sfruttato nell’industria fotografica, era spesso a buon mercato), che a sua volta ha aperto la strada alla diffusione di macchine fotografiche REN economiche e alla proliferazione delle immagini.

Inoltre, fin dalle sue origini, la fotografia è stata considerata metaforicamente una forma di valuta. Già alla fine degli anni cinquanta dell’Ottocento Oliver Wendell Holmes ha individuato un’analogia tra la fotografia e la duplice natura delle banconote, entità virtuali e materiali insieme. Le fotografie sono state utilizzate come sostituti degli oggetti che rappresentano e associate a sistemi di valore esistenti al di fuori dell’immagine. L’ambito in cui questo meccanismo è apparso più evidente è la pubblicità, che attraverso la fotografia ha ampliato il proprio raggio d’azione infiltrandosi allo stesso modo nello spazio pubblico e in quello privato.

Ciò che rende le fotografie risorse particolarmente versatili è la loro riproducibilità: possono essere facilmente usate, riciclate e riproposte in forme, luoghi e contesti diversi. Tuttavia, fuori dalla sfera artistica, le fotografie non hanno un valore autonomo. Il valore è dato dal lavoro necessario per produrre un’immagine e dai servizi e dalle infrastrutture che le vengono associati, come la definizione di criteri di selezione, la presenza di metadati qualitativi o l’organizzazione in database. Inoltre, l’uso e la circolazione continui sono fattori essenziali nella creazione del valore. Anche a livello semantico, termini come banca di immagini, fotografia stock, estrazione di immagini riflettono il legame tra l’organizzazione sistematica di informazioni visive e l’idea di valuta.

Con la fotografia digitale è cambiato anche il sistema di attribuzione di valore. Se il mercato delle immagini per la stampa e della fotografia stock è in declino dagli anni 2000, le immagini riconducibili a dati e metadati sono diventate la merce di scambio del capitalismo informatico, nel quale le fotografie sono sfruttate a molti fini diversi: influenzare i risultati delle ricerche, personalizzare la pubblicità, contribuire alla ricerca scientifica o alla sorveglianza. I servizi di social media in particolare sono piuttosto indifferenti alle fotografie che si accumulano nei loro server, ritenute utili solo per addestrare gli algoritmi di riconoscimento delle immagini. Tuttavia, le stesse società hanno interesse a monetizzare i dati raccolti attraverso le enormi quantità di materiale visivo caricato. Si potrebbe concludere che i dati generati da un’immagine hanno altrettanto valore dell’immagine stessa.

La photographie est un produit et un catalyseur de l’ère industrielle et postindustrielle. Dès ses débuts, le médium a documenté la croissance rapide des sociétés industrielles. Les photographies ont mis en valeur les possessions matérielles de la culture de consommation naissante. Elles ont contribué à promouvoir de nouveaux produits et documenté l’expansion des modes de transport, tels que les réseaux routiers et ferroviaires, ou l’empilement de marchandises dans des entrepôts destinés au commerce mondial.

Les premiers hommages à la photographie ont maintes fois souligné la facilité, la rapidité et l’efficacité avec lesquelles les images pouvaient être créées, ainsi que le large éventail de leurs utilisations potentielles. En outre, aux 19e et 20e siècles, les coûts des matériaux étaient plutôt bon marché grâce à l’exploitation d’une main-d’œuvre sous-payée. L’augmentation de la production industrielle de matériel photographique a ouvert la voie à la distribution d’appareils photo et de matériel d’impression à des prix abordables, ce qui a accéléré la prolifération des images. La photographie est devenue partie intégrante d’un système économique déterminé par l’offre et la demande, la circulation et l’investissement.

Dès ses débuts, la photographie a été comparée métaphoriquement à une forme de devise. À la fin des années 1850, le médecin et essayiste américain Oliver Wendell Holmes a établi un parallèle entre la photographie et le caractère double des billets de banque, à la fois entités virtuelles et matérielles. Les photographies étaient utilisées comme substituts des objets qu’elles représentaient, renvoyant à des systèmes de valeurs situés en dehors de l’image. Le domaine dans lequel ce phénomène est devenu central est la publicité, qui s’est développée grâce à la photographie, infiltrant la sphère privée et publique.

Ce qui fait des photographies des ressources particulièrement polyvalentes, est leur reproductibilité : elles peuvent facilement être utilisées, recyclées et apparaître sous différentes formes, dans différents lieux et contextes. Toutefois, en dehors du domaine artistique, les photographies n’ont pas de valeur en soi. La valeur est créée par le travail effectué sur l’image et les services et infrastructures qui l’entourent, comme la définition de critères de sélection, l’ajout de métadonnées qualitatives aux images ou leur organisation dans des bases de données. Par ailleurs, l’utilisation et la circulation permanentes sont des facteurs essentiels de la création de valeur. Le lien entre l’organisation systématique de l’information visuelle et l’idée de devise ou de monnaie se reflète dans des termes tels que les « banques d’images », les « photographies de stock » et « l’exploitation d’image ».

Avec la photographie numérique, les systèmes de valeurs associés au médium ont changé. Alors que le marché des images de presse et des banques d’images est en déclin continu depuis les années 2000, les données et métadonnées sont devenues une nouvelle marchandise du capitalisme des données, dans lequel les images sont exploitées à des fins diverses : pour influencer les résultats des moteurs de recherche, pour personnaliser la publicité, pour contribuer à la recherche scientifique ou en tant qu’outil de surveillance. Les réseaux sociaux, en particulier, ne s’intéressent guère aux images qui s’accumulent sur leurs serveurs, si ce n’est pour l’entraînement des algorithmes de reconnaissance d’images. En revanche, ils ont tout intérêt à monétiser les données qu’ils collectent grâce aux énormes quantités de matériel visuel téléchargé. Les données générées par une image, pourrait-on dire, sont devenues aussi précieuses que l’image elle-même.