ArticleVideo Games – (Photo)Realism – Photo(Realism)

Selim Krichane

Video Games – (Photo)Realism – Photo(Realism)

The video game at the intersection of different media

Video games have become a major cultural industry, playing a key role in the circulation of images and the configuration of our collective imagination. Backed by a cultural and economic history that spans more than fifty years, video games have always had an intense relationship with all the other audiovisual media around them. When the first home consoles appeared in 1972, video games relied on TV cathode ray tubes to arrive in people’s living rooms and produce images, as with the Magnavox Odyssey designed by television engineer Ralph H. Baer (1972).

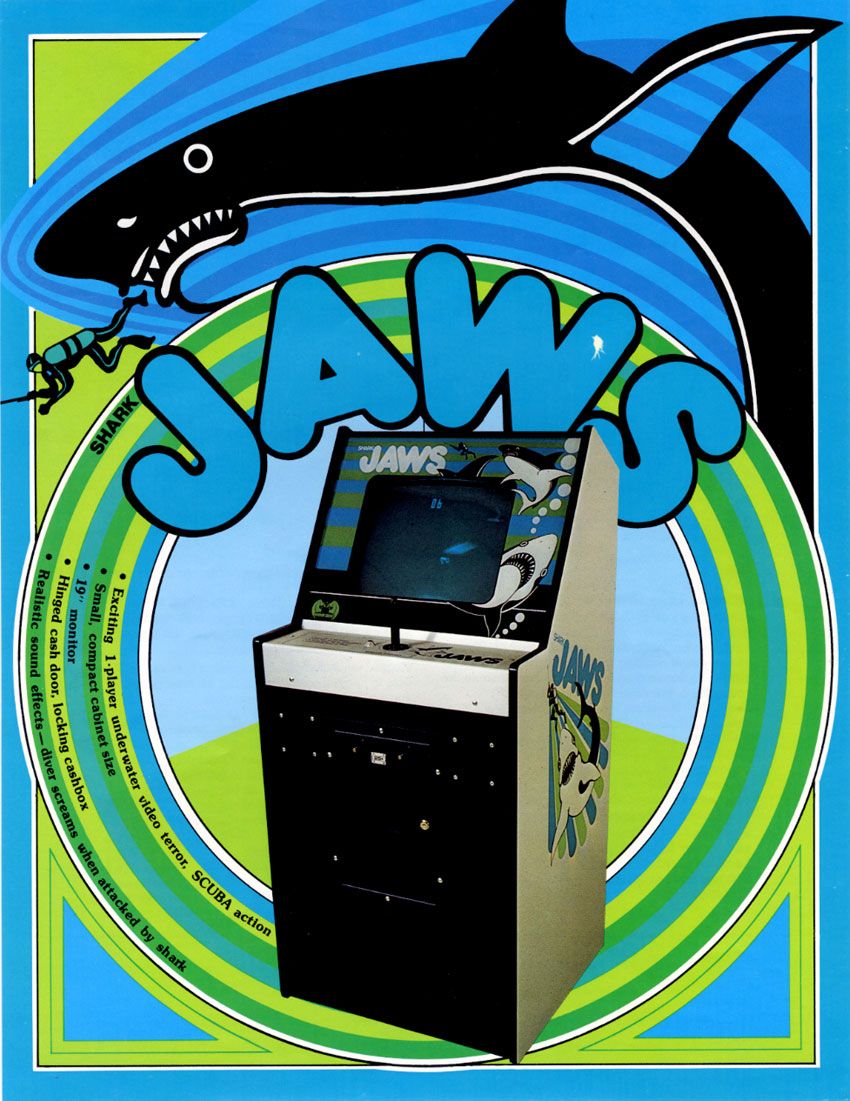

The cinematic/photographic image soon came to embody a model for the nascent video game industry. This was first of all because cinema and the images it produced constituted an invaluable cultural and symbolic point of reference that video game creators and manufacturers could rely on as a lodestar to guide the public’s reception of the games as a new cultural practice. Another reason was that the graphics capabilities of the first generations of video games in some cases meant that decoding and reading them required an external model to refer to. For instance, the first home consoles mostly adapted sports games (tennis, hockey, ping-pong) which typically aired on the same television screens. Adaptations of Hollywood films also appeared over the course of the 1970s – for example, the arcade game Shark Jaws marketed by Atari in 1975: although the company did not own the rights, it still went ahead and adapted the film Jaws (Steven Spielberg), which had its cinema release the same year.

Today, the ‘realism’ – or ‘photorealism’ – of video game images has become a truism in the discourses of promotion and reception surrounding the medium. We are accustomed to hearing that video games are now increasingly realistic, that their incredible precision puts them on a par with cinematic and photographic images and that recent developments in virtual reality mean that they can even compete with the pictures produced by our sense organs. Popular discourse seems to suggest that video games are destined to reproduce a certain way of seeing reality, with the cinematic/photographic image representing an essential point of reference.

In the context of this article, we intend to locate this idea, as well as the relationship between video games and (photo)realism, in a cultural history of the medium, involving, as a key component, the discursive strategies of promotion and reception that have gone hand in hand with it. In this way, we will see that although photorealism is one of the main visualisation methods in the history of video games, in reality it is just one of a variety of options within a wide array of aesthetic possibilities in the area of video games. Even within the prevailing mode of production, photorealism is no longer the one and only means of representation for a field of cultural production that has diversified a great deal over the last twenty years.

Photography and video games

Swiss photographer and film-maker Pascal Greco was due to go to Iceland in April 2020 to proceed with his photographic project documenting the island’s architecture. The first lockdown in March 2020 disrupted his travel plans. So Greco decided to buy a PlayStation 4 console (Sony) to help him through the first lockdown. It was then that he discovered the game Death Stranding by game designer Hideo Kojima. Death Stranding is a game of exploration and adventure that invites players to take on the role of a delivery man – Sam Porter Bridges, played by American actor Norman Reedus – in a post-apocalyptic world in which humans have taken refuge in military bases or insecure villages, while wraithlike creatures haunt the territory. Impressed by the realism of the depictions and the way the game’s fictional world approximated the natural landscapes of Iceland, Greco decided to try his hand at in-game photography. Realised in 2020, his work gave rise to a series of photographs – titled Place(s) and published in book form in 2021 – and a series of prints (10 × 10 cm). The resulting images of rivers and mountains, waterfalls and rock formations generated a peculiar feeling of realism. The photographer rightly points out that he wanted ‘the people who view these pictures not to have the impression that they come from a virtual world, but that they look real.’[1]

More broadly speaking, Greco’s approach is part of a practice of virtual photography manifesting as the kind of in-game photography that has developed over the last ten years, at the intersection of established artistic practices and gaming practices.[2]

Using a Polaroid camera to take pictures of a screen playing images from a video game may be a surprising development. However, adopting an approach of this kind is a response to certain social, technological and cultural developments that are bound up with the history of video games, as we shall see.

Firstly, such a practice is predicated on the pursuit of photorealism as a means to create the visual environment for video games. In its use of photographic textures, light simulation tools and 3D modelling, Death Stranding responds to the ‘cinematic urge’ that marks all of Kojima’s productions. Accordingly, Greco’s work is aligned with the same photographic ambition that is evident in the game, ‘bringing things full circle’, in a manner of speaking. Secondly, this photographic project is based on the presence of a ‘photo mode’ within the game, which allows the player to make their avatar disappear along with the interface elements (icons, gauges, mini-map, etc.) to simulate a situation in which a photograph is being taken. The process of integrating and simulating the photographic act in video games started in the late 1990s in games like Pokemon Snap (Nintendo, 1999) and Beyond Good and Evil (Ubisoft, 2003). In these examples, the option of taking photographs is a key mechanism in the game that replaces, in a sense, the action of aiming and shooting at in-game opponents. During the 2010s, when game consoles also became platforms for socialising and sharing content, the ‘photo mode’ spread within mainstream production to become a feature appreciated by a section of the gaming community.

The act of capturing an image during a gaming session, like a screenshot, feeds the processes of sharing and circulating content created by the communities of practice. This is a constituent element of contemporary media usages, which are characterised by a convergence of technologies and participative approaches.[3]

Given that Greco was able to pursue a photographic practice like this in 2020 and that such a practice is actually central to the regimes of sociability in video gaming, where the practice of taking and circulating gaming images has become standard, what are the historical factors that have led to these kinds of developments?

A historical perspective: game video, cinema, photo

The technological attraction of video games and the devices used to play them has been a framework for the medium’s promotion and reception since the 1970s. A frame of reference of this kind – one that showcases the graphics capabilities of consoles, the power of their processors and the quality of their graphics cards – represents a constant feature in the discourse of ‘techno-industrial glorification’, which has become normalised within the industry’s promotional discourse, fed by the main economic actors in the sector.[4] This discourse has a particular focus on the ‘realism’ of representations. We can find an example of this in the RealSports series of games launched by Atari in 1982. Although the American company’s first home console – the Atari VCS (or Atari 2600 in Europe) – had limited capabilities in terms of graphics, the promotional language used for these games highlighted their ‘realism’ both in terms of what they depicted and their simulation of the complexity of the sports in question. A 1982 advertisement, complete with photos, reads, ‘These pictures show you how incredibly life-like new ATARI RealSports video games look.’[5] Looking at the pixelated images of the 1982 RealSports Baseball game referred to in the ad, we can see the extent to which the issue of ‘realism’ is historically and discursively located. That said, this promotional strategy was picked up by journalists in the specialist press and by communities of practice during the 1980s. The issue of ‘realism’ would become even more important from the late 1980s on, owing to the technological and aesthetic convergences that would affect the video game and film industries.

The late 1980s were a watershed period for video game images as 3D graphics became increasingly widespread, recapitulating cinema’s linear perspective. This fragmented process was a feature of mainstream video game production throughout the 1990s. It depended in part on technical developments, such as enhanced computing power, increased storage space with the advent of optical media, and the development of video compression standards like MPEG-1. To start with, these modes of visualisation affected flight simulators and sports simulations in the late 1980s, before influencing all mainstream production.

The presence of video sequences, which might be pre-calculated 3D models (‘CGI’) or digitised live-action sequences (‘FMV’, which stands for ‘Full Motion Video’), became widespread in video games and was a new locus of technological attraction and a much-vaunted ‘photorealism’, which was focused on in promotional discourses. This period also witnessed the emergence of a new genre, the ‘interactive film’, a hybrid of the video game and cinema which made extensive use of live action material, as exemplified by Night Trap (Digital Pictures, 1993) and The 7th Guest (Tribolyte, 1993). This period of strong convergence between audiovisual media saw the spread of ‘remediation’ processes, illustrated by games like Myst, which, as David Bolter and Richard Grusin put it, combined ‘three-dimensional, static graphics with text, digital video, and sound to refashion illusionistic painting, film, and, somewhat surprisingly, the book as well’.[6]

The aesthetic codes of video games were then shaken up, particularly with the routine appearance of non-interactive sequences (‘cut-scenes’ or ‘trailers’) to punctuate the game activity, and with the spread of the ‘virtual camera’ as a point of view – sometimes controlled by the gamer – directed at the diegetic space of games modelled in 3D, which often made use of photographic textures. The commercial success of Sony’s PlayStation console, which came out in 1995, and Nintendo’s transition to 3D in 1996 (with the release of the Nintendo 64 console), completed this transition to three-dimensional graphics. This was coupled with the solid integration, in the discourse and frames of intelligibility associated with the medium, of evaluation criteria based on the ‘photorealism’ of the images.

From photorealism to diversified modes of representation

Historically speaking, the interactions and crossovers between the video game industry and the film industry, supported by television and TV depictions, helped make ‘photorealism’ a criterion that was used to assess and promote video game images. The increased interaction between these areas in the 1990s, in technical, economic and cultural terms, was of crucial importance in the aesthetic history of the medium. During the 2000s, this quest for photorealism continued with successive Sony console releases, PlayStation 2 (2000) and PlayStation 3 (2006–7): this was spurred on by the arrival of Microsoft on the home console market (Xbox consoles, 2001). Photorealism thus retained its place as a cultural and aesthetic marker, a means to evaluate (and promote!) the technical capabilities of computer hardware that is still used today.

However, the development of games for mobile phones from 2010 on and the emergence of an independent video-game production scene had a major impact, shaking up the norms of game imagery and leading to their diversification.

The success of mobile games was presaged by the fad for the Nokia phone Snake game that started in 1997 and reinforced when apps appeared that could be downloaded to so-called ‘smart’ phones: this success radically changed the way video games were produced and distributed – witness the examples of Angry Birds (2009) and Candy Crush (2012). Over the last ten years, the limited technical capabilities of telephones, as compared with home consoles or computers, have led economic players to focus on other visual modes in games and other ways of marketing them. Here, photorealism is not required; instead, the prevalent form is abstract and stripped-down graphics, coupled with the remediation of the norms of representation used in comics and cartoons. This evolution in game platforms and practices has gone hand in hand with a reorganisation of the ways games are created and distributed. The advent of online distribution platforms like Steam (Valve, 2003) and the PlayStation Store (2006), which were controlled by the economic heavyweights in the sector, also led to the emergence of an independent production scene consisting of small development studios with limited financial resources at their disposal.

Enabled by the Internet, the electronic sale and distribution of games now easily predominate, facilitating the participation of these minor economic players. The independent scene, which profits from and feeds the process that gives cultural legitimacy to the medium, has also had an impact on the way video games are displayed. In many cases, ‘Indie Games’ – to give them their proper name – opt for pared-down graphics and styles that fall within ‘Pixel Art’, i.e. the 2D representation of the graphic elements of the game world using rasters of visible pixels, in reference to the game aesthetics of the 1980s. With limited means and teams of fewer than ten people, it is difficult to compete on the terrain of hyperrealism and emulate the Assassin’s Creed series (Ubisoft, 2007) or Horizon (Guerilla Games, 2017).

Consequently, video games now bring together a huge range of objects, cultural practices and technical platforms. While photorealism is still a dominant mode of visualisation in video games, many producers opt for alternative modes, such as the cartoon quality of Nintendo productions (Mario Odyssey, Switch, 2017), the abstraction of certain games of skill or puzzle games (Super Hexagon, Terry Cavanagh, 2012; Glitchspace, Space Budgie, 2016) or pixelated graphics (Celeste, Maddy Thorson & Noel Berry, 2018).

Video game images

After this brief historical overview, let us return to the contemporary practice of in-game photography. It is striking to note that the artists practising it today, such as Duncan Harris, Leonardo Sang or Pascal Greco, mostly opt for games with a strong sense of photorealism (Fallout 4, 2015, Control, 2017, Ghost of Tsushima, 2020). Besides having a ‘photo mode’ that makes it much easier to capture images, these games also display a density and visual richness that explains the remediation of the photographic act and permits a multitude of choices to be made in selecting the subject, frame, lighting, etc.

The commercial history of the video game now spans half a century. Against this background, the practice of in-game photography indicates the cultural and social importance of the medium. Through it, the captured image – based on the historical model of photography – facilitates interactions and allows memories to be concretised, while making it possible for traces of the game activity to circulate on digital networks, benefiting the communities of practice and the economic players in the industry.

In-game photography also illustrates the complexity of the interactions and influences at work in the present-day world of audiovisual media. Given its symbolic value, the photographic imprint has played a critical role as a model for how video games have been displayed since the 1980s. For the last ten years, photographic practice has been re-establishing a connection with the video game, but this time it has captured it from the outside, as the very subject of its recording, taking advantage of the density and richness of its images, which the games owe, in part, to their distant cousin: photography.

[1] Pascal Greco, Place(s), Geneva: Chambre Noire (2021), n.p.

[2] Nathalie Dassa, The Imaginary Worlds of In-Game Photography, in: Blind Magazine, 5 January 2022, https://www.blind-magazine.com/stories/the-imaginary-worlds-of-in-game-photography/.

[3] Henry Jenkins, Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, New York: New York University Press (2006).

[4] Martin Picard and Carl Therrien, ‘Techno-industrial Celebration, Misinformation Echo Chambers, and the Distortion Cycle: An Introduction to the History of Games International Conference Proceedings’, in: Kinephanos: Journal of Media Studies and Popular Culture (January 2014), http://www.kinephanos.ca.

[5] ATARI RealSports advertisement, accessible at www.atarimania.com.

[6] Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediation: Understanding Media, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (1999), p. 94.