ArticleModelling Specific Realities: On the Implications of Simulation Technologies

Raymundo Stadelmann

Modelling Specific Realities: On the Implications of Simulation Technologies

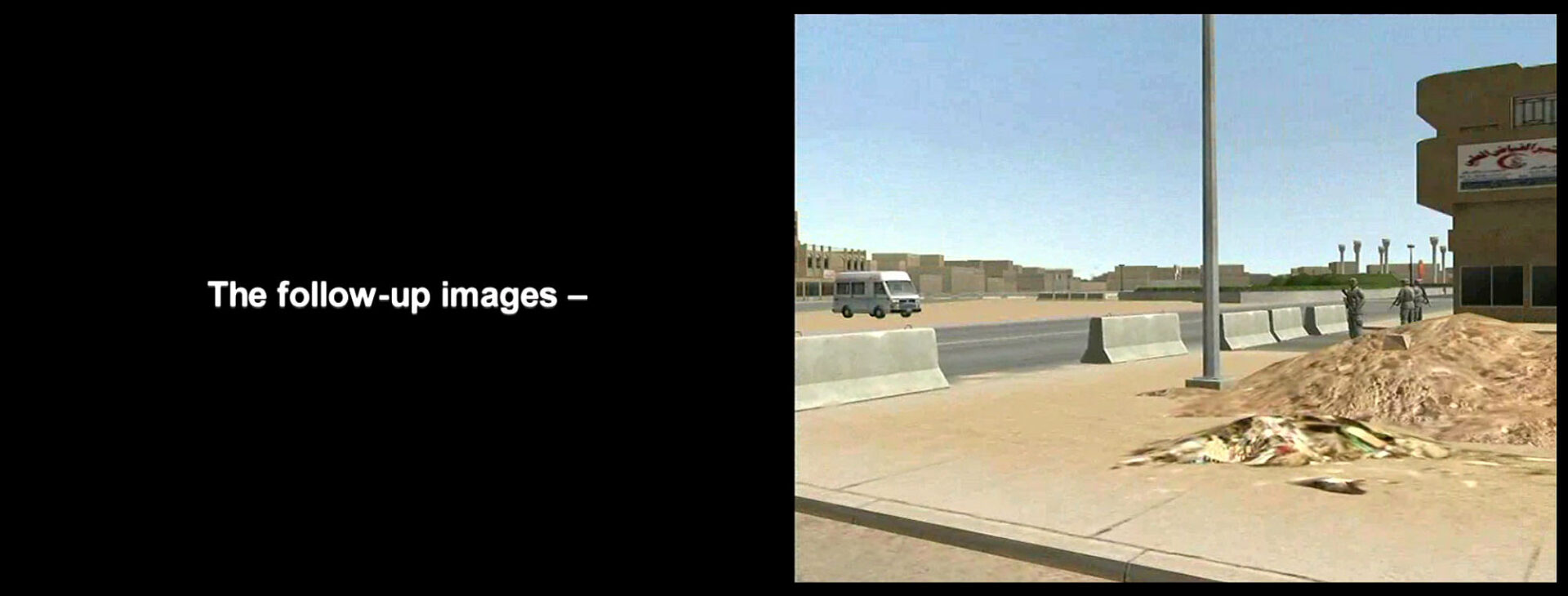

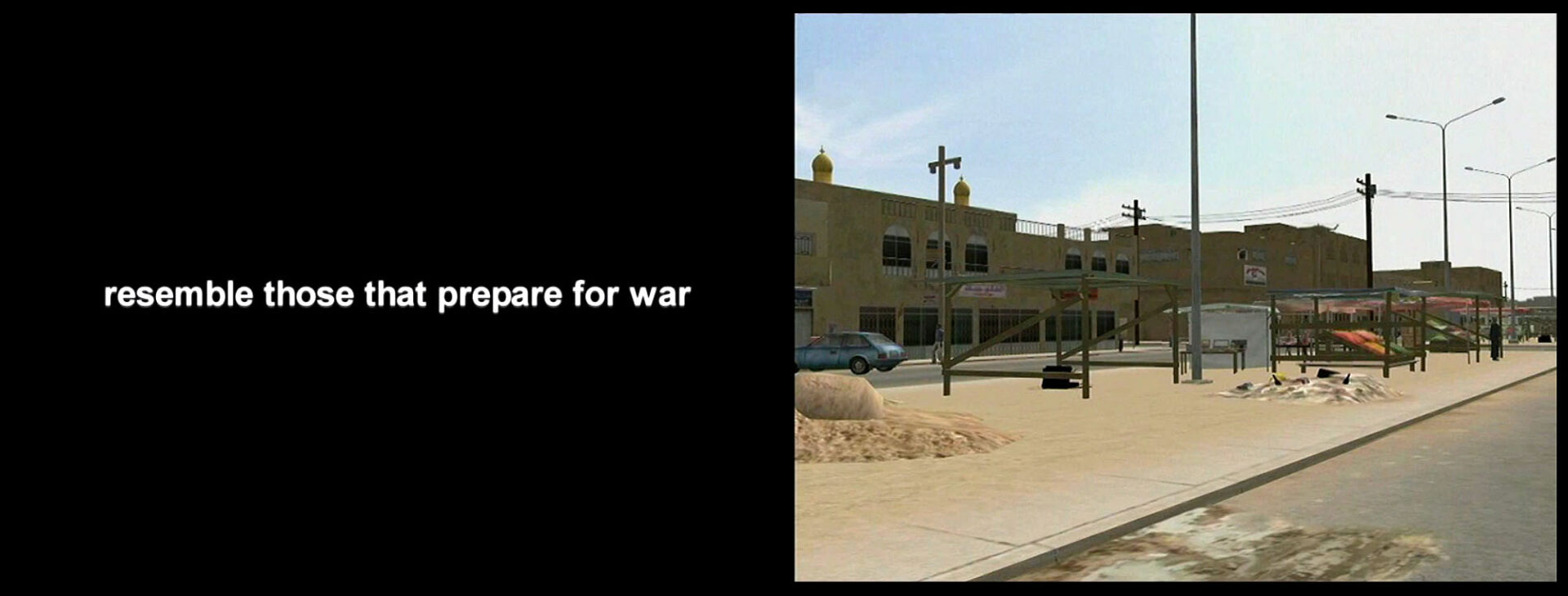

A virtual drive through the desert landscape in an armoured vehicle reveals a cartographically calibrated model world. An instructor introduces obstacles, weapons and enemy figures on the screen and supplies them with different equipment with a click of the mouse. Harun Farocki’s multichannel installations Ernste Spiele I–IV (Serious Games I–IV) (2009–10) show the training that US soldiers received before being deployed in the Iraq War and scenes from their subsequent treatment for PTSD. Farocki intersperses the material with white titles inserted on a black background that refer to the images that come before and after. ‘The follow-up images – / resemble those that prepare for war.’ The intertitles refer not just to the virtual simulations but also to the real world of military exercises. For the virtual model world that is presented reconstructs memories of the war while also designing the real world after the war.[1]

Farocki’s footage from various US military facilities shows young soldiers being trained with computer software. The Virtual Iraq program was used to prepare soldiers for war, to rehearse military scenarios and to recreate them after the event.

Shots of a MOUT (Military Operations in Urban Terrain) site takes the idea of ‘indistinguishability’ to the extreme. Not only is it almost impossible to tell the constructed training facilities apart from Virtual Iraq but we can also see how the real world strives to emulate the simulation.

These feedback loops – a focus of Farocki’s study – can be seen as an extension of something he has termed ‘operational images’. These are images that are not, in the first instance, intended for contemplation but are instead crucial to the processing of information within technical (for example, military or medical) visual operations. They increasingly redefine what an image is in a society that is now permeated by visual media. Farocki’s research confirms the fact that images no longer seek to represent the world but rather actively intervene in it. The image is no longer a reproduction but has become an autonomous reality, an intervention in visual worlds that are constantly being refreshed. This leads to a reversal of the logical and temporal relationship between image and reality. Images are now their own models, uncoupled from reality – an anti-mimetic condition that Jean Baudrillard called ‘the divine irreference of images’.[2] But how does Baudrillard arrive at the radical conclusion that it is ‘the reference principle of images which must be doubted, this strategy by means of which they always appear to refer to a real world, to real objects, and to reproduce something which is logically and chronologically anterior to themselves’?

Simulation or Virtualisation?

The tragic fire in Paris’s Notre Dame cathedral is a pertinent example of how the virtualisation of a cultural building with – more than just – national significance can enter reality through the back door. French President Emmanuel Macron’s emotionally charged tweet (‘I am sad to see this part of us burn tonight’[3]) helped galvanise a sense of identity: it was followed by various pledges of aid and donations from billionaire companies like L’Oréal and Louis Vuitton (LVMH), which immediately triggered a debate in France about donations in general. In the public discourse, the offering of the French video game company Ubisoft got drowned out by the debate over the most peculiar restoration proposals and the criticism of PR campaigns worth millions in the form of donations. For a short time, the video game developer and publisher augmented its financial contribution to the restoration of Notre Dame by making its virtual models of the building – which are the setting for the video game Assassin’s Creed Unity (2014) – available for free download. The accuracy with which Ubisoft brings historical scenes back to life is well-known among gaming fans and can be characterised very much as a love of detail. There has been some speculation about whether the video game producer might be of assistance in the reconstruction process in another capacity: by making the data compiled for the construction of the virtual model available for use in reconstructing the original building. Responding to an enquiry from the Guardian newspaper, a Ubisoft spokesperson reported that this was not currently the case, ‘but we would be more than happy to lend our expertise in any way that we can to help with these efforts’.[4]

Ubisoft’s model was recreated by senior level artist Caroline Miousse using various documents, photographs, scans and drawings. She spent fourteen months reconstructing the cathedral, which had to be transposed to the condition it was in, in around 1790; this applied not only to the architecture but also to the paintings, the furnishings, the fabrics and banners. A reconstruction of this kind – which turns out to be a stumbling block, even for art historians – would seem to be an insurmountable challenge for a level developer who had never visited the cathedral in person prior to the game’s release and impossible to accomplish flawlessly.[5] For Ubisoft, the idea was for the world-famous cathedral to establish itself as a new benchmark for photorealistic video game worlds. As if this were not a big enough challenge, Miousse had to take a number of liberties in order to make Notre Dame ‘playable’, which meant creating new routes and scaling or shifting certain objects. In addition to this, some of the works of art in the cathedral are protected by copyright – including the monumental stained-glass windows: this meant the developers got ‘to put a little bit of [their] own identity on an iconic monument’.[6] Evidently the producers did not seek to scientifically reconstruct the cathedral in the game: this was not their ambition, nor was it within their power to do so. ‘Since I had never been formally taught, I had to figure things out on my own to recreate Notre Dame’s structure in the most realistic way possible.’[7]

It is hard to imagine what a sacred building bearing the Ubisoft developers’ ‘own identity’ might have looked like, and what identity (‘this part of us’) the reconstruction would have espoused had a commercial video game company played a major role in rebuilding the cathedral. But more interesting than speculations about how the architecture might have been realised is the fact that these virtual models can be consulted at any time and are only one decision away from being turned into reality. This brings up questions about the status of these kinds of models.

In game studies there has been lively discussion about how virtual worlds should be characterised and what we should expect of them. The word ‘simulation’ should be treated with particular caution, because ‘simulations cannot stand alone, for their conceptual status is dependent on the something of which they are imitations’.[8] Veli-Matti Karhulahti’s suggestion is to use the term virtualisation for computer-generated game worlds, as it is not based on an empirical reference system (real – virtual). In light of the example above, however, I would like to explore the question of what status the virtual model takes on when it goes a step further and serves as a model for the real. For if we remain with the computer game industry, while abandoning the ludo-scientific perspective, it soon becomes apparent that virtualisations are not in any sense models in an insulated virtual environment. What status would the real, reconstructed Notre Dame have if it had been built by Ubisoft on the basis of a virtualisation? What if the game (or the virtual environment) is not based on empirically compiled data (virtualisation), and reality is modified as per the virtualisation? Do reality and simulation then change places in terms of their conceptual status?

Unreal Engine – ‘Let’s get serious’

For the video game community and the commercial music landscape one of the highlights of the nearly two-year period during which major events were disrupted by the pandemic was Travis Scott’s live performance on the virtual stage of the popular video game Fortnite (2017). Over 12.3 million people congregated for this historic moment, coming together to watch the world’s largest live music performance to date on the video game platform created by US software company Epic Games. The company, which started doing business in 1991, used virtual galaxies and underwater landscapes to transform the setting of the shooter-based online game into a monumentally orchestrated attraction with seductive allure. There is, first up, no evident connection between the shooter game and the US rapper, but it is clear that their commercial tie-up calls into question previous conventions (be it the idea of the stage or a hermetic computer game community) and generate new spaces for themselves. And like any space that relies on infrastructure, the virtual space invariably has a political dimension.

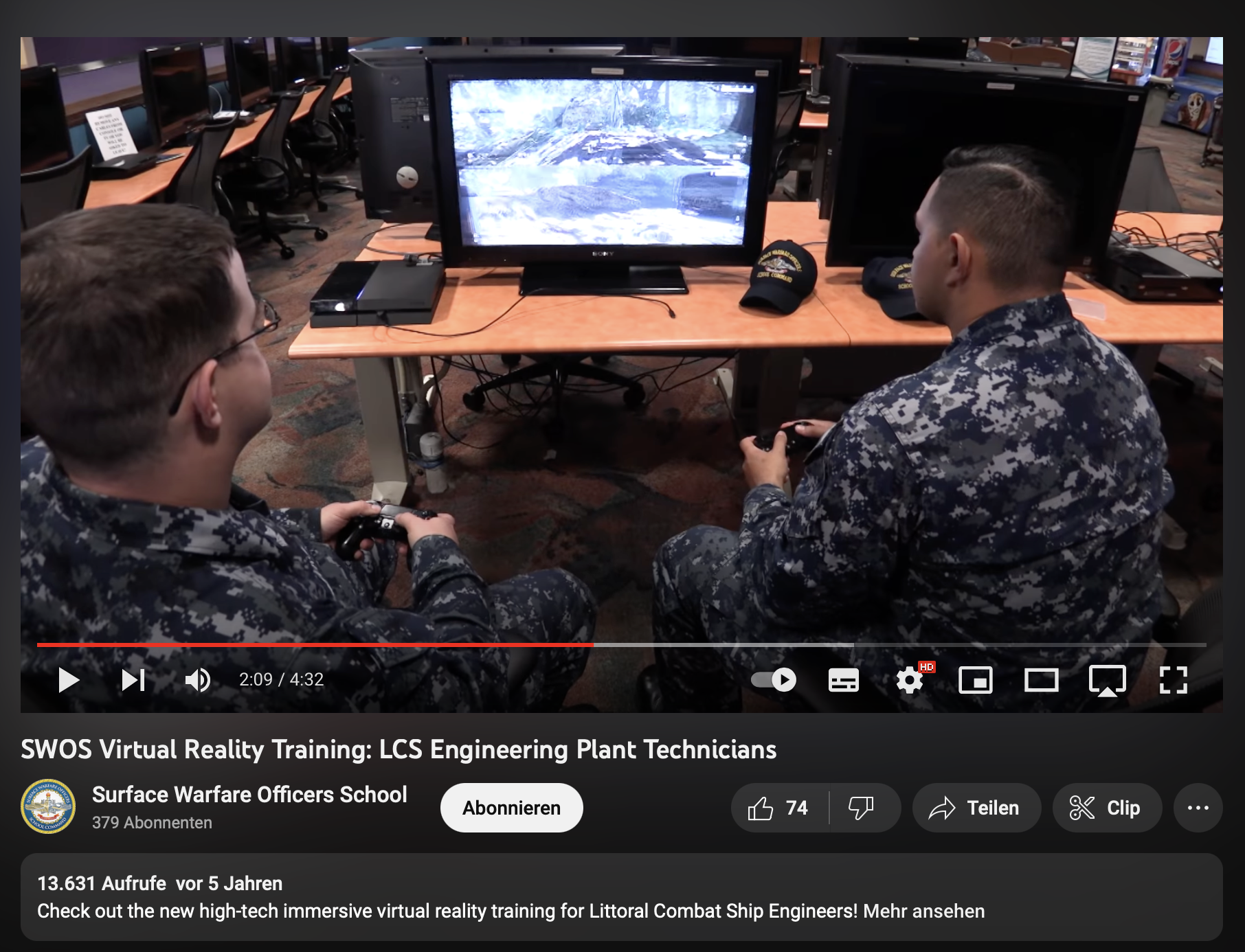

One of the engine’s customers and users is Cubic Global Defense, a subsidiary of Cubic Corporation. The company, which specialises in virtual combat simulators and training systems, supplies technical support to the US military and allied armies. This includes using the Unreal Engine 4 to help develop systems and services for ‘performance-based training, scalable training architectures, air combat training, and high-fidelity combat training’.[10] For example, the SWOS (Surface Warfare Officers School) crew is not trained on board but directly on a virtual clone of the ship. Besides being economically expedient, virtual training also has the advantage of using media technologies that the crew are already familiar with anyway.

‘Younger sailors today, as they come on board, you know, they’re so familiar with video games that it helps them so much when they come into a classroom environment where they can go through a virtual reality which is similar to video games and they remember a lot more of what they do through the virtual reality than the normal legacy teaching that we used to do.’[11]

Although there may be a number of perfectly obvious reasons – including risk mitigation and economic or ecological concerns – to explain the general prioritisation and shift in the direction of visual media technologies, they still require a new balance to be struck. If the process of training a ship’s crew is now a purely virtual affair, reality has become the exception. When reality is supposed to operate as much as possible like the simulation, convergence strategies must ultimately be applied to bring it more and more into line with the simulation. This involves minimising the factors that generate too many discrepancies. In an ideal situation, there would be no distinction between simulation and reality. This is not a new issue that is only now being flagged up by the entertainment industry – it has long been known about in business informatics. For one thing, there is a considerable cost advantage to using simulation technologies. ‘At the same time, it is hard to ensure the necessary isomorphism between the system and the model to be created that will yield valid knowledge about the real system.’[12] Because the simulation models can only ever be as good as the operating system and the availability of data will allow (and cannot permit any significant variances as a result), the – disruptive – factors are reduced to a level that can be computed by the system. I have tried to trace how these kinds of convergence strategies occur outside the realm of business informatics and to map the effects they can have on the aesthetics of the media. The final step is to demonstrate why the study of simulation technologies is particularly fruitful from the point of view of photography or, more precisely, image theory and thus align myself with the tradition of Farocki and Vilém Flusser, who have never underestimated the interventions of nondescript image operations within complex systems relating to the technology and ecology of media.

‘Photography, the mother of all things’

It may be that in post-history, photography (and the technical images that are heir to it) performs the same function in society that war did: that of rupturing processes. In the dawning age of virtual spaces, it is possible that photography and not war is at the origin of all things.[13]

When Flusser talks about photography (and the technical images that are heir to it), he goes far beyond the supposedly representative nature of the visual medium. He introduces the idea of the techno-imagination, which he regards as distinct from the imagination of traditional images: he uses it to show that reality itself is a computation – with photography the first ‘step toward the synthetic production of objects from grains’ – while the ‘distinction between image and object, between fiction and reality becomes increasingly non-operational’.[14] Flusser describes photography as a force that is at once creative and destructive, making fiction and reality indistinguishable in history and leading to the ‘unstoppable disintegration of the world of objects and its subject’.[15] While propositions of this kind are generally located in discourses around digitisation – and the accompanying displacement of concrete lifeworlds into digital environments – this essay is designed to examine, à la Flusser, how current imaging processes are transforming our present. However, the fact that today’s radical imaging processes are worlds away from the historical narrative of photography does not make them any less a subject of photographic theory. For just as Flusser argued the case for a philosophy of photography to study the overlap between fiction and reality, Joanna Zylinska makes a stand for an expanded concept of photography when she describes it as a ‘technology of life’.[16] Photography does not just represent life, it actively moulds, regulates and documents our everyday world: ‘Photography has become pervasive and ubiquitous: we could go so far as to say that our very sense of existence is now shaped by it.’[17] This approach is also associated with the critique stating that prior discourses in the humanities on the subject of photography are insufficient if we want to get a proper understanding of photography – and thus of image operations too.

In line with this, my proposal is to include simulations in the ‘historical totality of photographic forms’.[18] The subject of this work, then, was visual products that lay claim to reality but are not necessarily based on the processes of photographic optics. For a simulation is not meant to record a moment of reality – although it is questionable whether photography has ever done that – but rather serves to create a model, a ‘pre-imaging’, of a future reality (whether or not it actually occurs) from real data: it is the emulation, the ‘post-imaging’, of real scenarios for a variety of purposes. Accordingly, this essay sets out to delineate various interactions between reality and virtuality by presenting current simulation technologies and theories. Simulation is a particularly good locus for reflecting on this apparent dichotomy, as inevitably it is itself an object of both poles: it uses data – that has been harvested from the empirical world – to create new scenarios, which can be described first up as visualisations. However, if the data were not obtained from empirical reality, the simulation would be nothing more than a fiction. The reverse is also true: if the simulation is not embedded in the virtual, it is already reality.

It is still important to consider whether the ‘dawning age of virtual spaces’ has already arrived and ‘photography and not war is at the origin of all things’.[19] The discovery that technological advances in the realm of ‘virtual spaces’ benefit from the dialogue and close collaboration between the military machine and simulation developers is indicative of the proximity of the two phenomena (war and photography). We have focused on simulation technologies because, unlike other imaging processes, they make no pretence of capturing (after-)images of familiar realities; rather, they are used to generate (pre-)images of specific realities. Works like those of Harun Farocki or the cutting-edge technologies of Epic Games show that model worlds situated in a purely virtual realm do indeed extend beyond the designated programs. However, the theoretical implication of this is that the status of what is simulative and what is real is being destabilised. A thought experiment of this kind has been carried out in respect of Notre Dame. If we downgrade simulations or virtualisations as representations of objects from the real world, we underestimate the power they have to affect us. But if we view these imaging processes as interventions in real imagery and the real world we live in, it is possible to map out their aesthetic effects as media phenomena – as Farocki’s work serves to remind us. The final step in fully appreciating these constructed image worlds involves examining strategies for bringing the concrete world into convergence with simulated reality and looking at where such practices occur. In the future, will MOUTs or SWOS fleets be built to align with the capacities of simulation programmes to allow performance-based training to be optimised? Or, to put it another way, at what point will it become easier, economically and environmentally speaking, to realise the simulation instead of reconstructing the reality? These are questions that can perhaps only be answered when the technological advances have manifested and would seem to remain, therefore, in the realm of speculation. However, these new worlds of images, along with the new lifeworlds they give rise to, also create a new relationship between image and reality. In this respect, we are also faced with the emancipation of the image from any referential constraints, as we move in a direction that Flusser astutely foresaw when he maintained that photography and not war seems to be at the origin of all things.

[1] For a more in-depth analysis of Farocki’s work, see Christa Blümlinger, ‘War as a Challenge to Digital Realism’, in: Harun Farocki: Soft Montages, ed. Yilmaz Dziewior, Bregenz: Kunsthaus Bregenz (2011), pp. 34–47.

[2] Jean Baudrillard, ‘Simulacra and Simulations’ in: Selected Writings, ed. Mark Poster, trans. Paul Foss, Paul Patton and Philip Beitchman, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press (2001), p. 170.

[3] Tweet from 15 April 2019, https://twitter.com/emmanuelmacron/status/1117889484358426625?lang=en (accessed 15 June 2022).

[4] From the article by Keza MacDonald, ‘Assassin’s Creed creators pledge €500,000 to Notre Dame’, in: The Guardian, 17 April 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/games/2019/apr/17/assassins-creed-creators-pledge-500000-notre-dame-restoration.

[5] Interview with Caroline Miousse, conducted by Tara Long, https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x280dne (accessed 15 June 2022).

[6] Brett Makedonski, ‘One Dev Spent Two Years Making the Notre Dame in Assassin’s Creed Unity’, in: Destructoid, 16 April 2019, https://www.destructoid.com/one-dev-spent-two-years-making-the-notre-dame-in-assassins-creed-unity/.

[7] From the article by Keza MacDonald, ‘Assassin’s Creed creators pledge €500,000 to Notre Dame’, in: The Guardian, 17 April 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/games/2019/apr/17/assassins-creed-creators-pledge-500000-notre-dame-restoration.

[8] Veli-Matti Karhulahti, ‘Do Computer Games Simulate, After All? Reconsidering Virtuality’, The Philosophy of Computer Games Conference, Istanbul (2014), n.p.

[9] ‘Let’s Get Serious’, Unreal Engine, https://www.unrealengine.com/en-US/solutions/training-simulation (accessed 5 March 2020).

[10] ‘Training’, Cubic, https://www.cubic.com/solutions/training (accessed 15 June 2022).

[11] Rasheed Brown, in ‘SWOS Virtual Reality Training: LCS Engineering Plant Technicians’, Surface Warfare Officers School, 27 June 2017, YouTube video, 2:04–2:21 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k-aT90ehH8Y.

[12] Wilhelm Dangelmaier and Christoph Laroque, ‘Simulation’, Beiträge von A–Z, Enzyklopädie der Wirtschaftsinformatik, 8 April 2019, https://wi-lex.de/index.php/lexikon/technologische-und-methodische-grundlagen/simulation/.

[13] Vilém Flusser,‘Fotografie, die Mutter aller Dinge’, in: Fotogeschichte: Beiträge zur Geschichte und Ästhetik der Fotografie 12/43 (1992), pp. 3–4, here: p. 4.

[14] Vilém Flusser, Vom Subjekt zum Projekt: Menschwerdung, Frankfurt am Main: Fischer (1998), p. 19.

[15] Vilém Flusser, Vom Subjekt zum Projekt: Menschwerdung, Frankfurt am Main: Fischer (1998), p. 21.

[16] Joanna Zylinska, Nonhuman Photography, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press (2017), p. 2.

[17] Joanna Zylinska, Nonhuman Photography, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press (2017), p. 2.

[18] On this, see Peter Osborne, Infinite Exchange: The Social Ontology of the Photographic Image, in: Philosophy of Photography 1/1 (2010), pp. 59–68. ‘Photography, like art, is a historical concept, subject to the interacting developments of technologies and cultural forms (that is to say, forms of recognition); increasingly, developments within photography, along with digital-based image production more generally, are driving the historical development of art’ (p. 61).

[19] Vilém Flusser,‘Fotografie, die Mutter aller Dinge’, in: Fotogeschichte: Beiträge zur Geschichte und Ästhetik der Fotografie 12/43 (1992), pp. 3–4, here: p. 4.