ArticlePhotography as the Currency of Social Capital

Matthias Pfaller

Photography as the Currency of Social Capital

1. The Scope of Photography

‘Just don’t be frugal with the number of copies … as it will sow a good seed.’ Alfred Krupp, 1875[1]

The Friedrich Krupp Corporation was founded as a producer of cast steel in the German city of Essen in the second decade of the nineteenth century. After the turbulent first years, the founder’s son, Alfred Krupp, rode the wave of industrialisation by building railways and weapons and turned the company into one of Europe’s largest industrial complexes, in the process becoming one of the richest men on the continent. Besides being a knowledgeable engineer and talented businessman, he had a gift for marketing. According to historian Bodo von Dewitz, Krupp was always preoccupied with the company’s public image. He travelled all over Europe to meet potential business partners and personally oversaw the production of promotional material, obtaining the decisive lead in a competitive industry.[2]

An integral part of his strategy was photography. He not only employed photographers, as other companies did, but established an entire photography studio, the Graphische Anstalt (graphic department) in 1861. The main motif of his promotional images constituted views of the factory buildings, collaged on, and distributed as, business cards typical of the time. Yet again, Alfred Krupp went a step further and had his photographer Hugo van Werden make panoramas from a central tower of his growing industrial complex, overlooking its entire expanse. As the views were regularly updated, the distant horizon with fields and villages was eventually consumed by more and more Krupp infrastructure. Krupp’s stand at the 1867 Paris World’s Fair was dominated by a cannon and a spectacular 360° panoramic image that was over seven metres in length. The photographs were a self-confident statement of the capacities of the company, and the size of the regularly updated panoramas reflected the company’s position as a European leader in steel production.

Alfred Krupp invested a considerable amount of time, money, and infrastructure on photographs of his business, calling them ‘a good seed’ for the promotion of his products and for building business relationships. In the following, I present some of the strategies he and his successors pursued to accrue social capital with photography. As a surrogate not only of the object it depicts but also of the relations that led to its capture and exchange, the photograph became a form of currency in the value system that shaped Krupp’s business and the global arms trade.

2. Photography as Social Capital

Photography at Krupp was not only an engineering or industrial affair, it also had several social levels, from employment to surveillance to business relations. Starting out in 1861 with Hugo van Werden, the Graphische Anstalt soon expanded exponentially, from one additional photographer and four workers in 1862 to 52 employees in 1890, almost 100 around 1900, and 200 in 1905.[3] Photographers, printers, bookbinders, and accountants found full-time work to satisfy the company’s growing need for pictures and an editorial staff.

For the large panorama of the factory complex, Alfred Krupp also mobilised his steel workers. In 1867, he gave orders for the views to be photographed on a Sunday, when the factory was idle – this meant that the photographers would not be disturbing production and there would be less smoke coming from the chimneys to cloud the view. Still, he wanted the images to look like a normal day of operations and suggested that workers come in (with compensation) to populate the scene: ‘I leave it [to the photographer to decide] if we need 500 or 1,000.’[4] The ease with which Krupp could order 1,000 workers to come to the factory on a Sunday demonstrates the hold he had over his staff and the financial investment necessary to produce the imagery he envisioned.

Ten years later, Alfred Krupp started an initiative to make portraits of all his employees. While higher-ranking staff were occasionally photographed for publications or commemorative events, the systematic compilation of workers’ images was not a philanthropic project designed to foster the ‘Krupp Family’ as is often assumed. Quite the contrary: writing to his secretaries from his English summer retreat in Torquay in 1871, Krupp stated that he wished to ‘establish for good the photographing of all workers to achieve tighter control over the people, their past, their doings and their lives. We must have our own private police force, which is to be better instructed than the city’s.’[5] For Krupp, the surveillance of workers was a key function of photography as an information technology. Moreover, it demonstrates the scale of his ambitions for photography: at the time of his death in 1887, he employed more than 20,000 people; by the time of the death of his son Friedrich Alfred died in 1902, the number had risen to around 50,000.

Although the workers’ portraits were never fully realised, the Graphische Anstalt expanded its production to an array of promotional material for newspapers, industrial fairs and more personal use. The photographic album, in particular, became a medium that was used to serve many different purposes. Typically, this was a fairly elaborate object produced in small numbers or as unique items; Krupp, however, had the Graphische Anstalt print entire editions on industrial products and views – these were sometimes made to stock in case business representatives spontaneously required a gift for customers. While in most regards Alfred Krupp pushed for efficiency and avoided unnecessary expenses, his marketing seems to have been more liberal: ‘A few thousand thaler more are of no importance.’[6] Photographic albums were an integral part of business negotiations, either in establishing contacts, positively influencing the outcome of deals in progress or strengthening existing relationships.[7] In this case, too, Krupp tended to micromanage processes, telling his agents to use the album as an icebreaker to facilitate small talk, rather than directly starting conversations with product descriptions and prices.[8] Yet, the scale on which photographic products were made does not indicate that this was a matter of mass production but merely demonstrates the size of the company. Krupp did not serve a mass market but rather an elite group of clients consisting of governments, military agencies and railway companies. Hence, the albums were mostly custom-made, adapted to certain geographical markets and lavishly embellished. Especially luxurious albums were given to the Brazilian Minister of War Hermes Rodrigues da Fonseca, the Austrian Archduke Franz Salvator and the German Kaiser Wilhelm II and included the programmes of events accompanying their grandiose visits.[9] The photographic albums, particularly the ones dedicated for specific people, were intended to build a personal connection between the Friedrich Krupp Corporation and its customers that went beyond a mere value-for-money rationale. This was an active policy pursued by Alfred Krupp and his successors, who hosted high-ranking clients and gave balls in their palace to the south of Essen, which was built in 1873. Kaiser Wilhelm II was a frequent guest and paid eleven visits to Villa Hügel, staying in his own apartment in the large complex. While there are no photographs of these private visits in the archives of the imperial court or the company, the regular inspections of guns by Prussian generals and the kaiser were duly recorded. For the Krupps, the social capital of knowing their select customers well was vital in keeping up sales and thus expanding their business capital.

The Krupps were, of course, not alone in using photography to express social relationships. Foreign clients, in particular, would send albums with views of their countries to Essen after returning home from a successful business trip. The so-called travel albums are the second most numerous among the albums preserved in the Krupp archive.[10] This practice shows that it is not necessarily photographs depicting individual people that foster personal relationships and business ties. Rather, it is the exchange of photographs in general that keeps the connection active. Photography here functions as a token of attention and thus as the currency of communication.

3. Participating in Global Capital: The Arms Race between Chile and Argentina

Besides illustrating the relationships between vendor and buyer, the photographs from the Krupp archive also provide information about the relationships between different clients. This is of particular interest since the Krupp company made almost half of its profits from war machinery in 1902.[11] The Prussian military was an obvious and important customer, yet Krupp sold to anyone with the means to buy. Indeed, the relationship between the arms manufacturer and the Prussian state is a large and complex topic, which shall only be hinted at here. Relatively early, at the Paris World’s Fair in 1855, German companies had individual representations, in contrast to their competitors from France and England, who appeared together in pavilions provided by their countries.[12] In 1936, however, to mark the 75th anniversary of the Graphische Anstalt, Krupp issued a short history of the company that closely aligned itself with events in Germany, from Wilhelm I’s coronation to the Franco-Prussian War and the First World War.[13] Inevitably, Krupp has been perceived as a German company and it presented itself as such, but at the same time it was not bound to its government and consciously assumed its position as a global player.

This flexibility is demonstrated by Krupp’s marketing strategy following the defeat of France in 1871. The company launched an extensive campaign advertising its artillery, which helped Prussia win the war. Krupp gave orders, once again, for photographic albums to be sent out to ‘states, governors, and khans’ to promote the effectiveness of his weapons.[14] Naturally, arms producers could not base their business entirely on the state they were operating in, as this would limit their market and subject their success to that country’s diplomacy and military luck. Simultaneously, states could not afford to only buy from domestic producers, as companies in different countries specialised in different types of weapons with varying degrees of quality. Despite this pragmatic reasoning, it may still appear counterproductive for one state that other states should have access to particularly powerful military technology – in this case, Krupp’s artillery.

Nevertheless, the international arms industry found an argument to not only justify weapons exports but also make it a matter of national interest. As Jonathan Grant writes, ‘By selling armaments to the periphery, firms pursued their own economic interests while convincing their home governments that such sales represented national prestige and could be used as a tool for exercising controlling influence in foreign countries.’[15] This type of control did not always come into effect and Grant continues to analyse examples where arms exports even enabled some peripheral countries to successfully resist Western colonisation. More often than not, as elaborated below, control was most effective when exports were blocked. Notwithstanding, the strategy of the arms manufacturers was a resounding success. To stick with our example, Krupp shipped artillery to half of the world, to countries like Afghanistan, Argentina, Austria, Brazil, Chile, China, Italy, Japan, Mexico, the Netherlands, Romania, Russia, Siam (Thailand), Spain, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

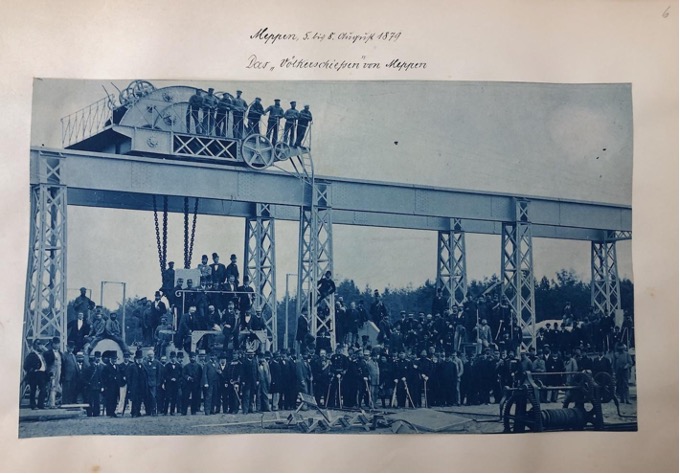

Krupp’s wish for entrepreneurial autonomy also manifested itself in the construction of several shooting ranges. Prior to this, the company had used Prussian army facilities to test its cannons but ultimately wanted to be free from the military’s administrative constraints. It also allowed the installation of a permanent and custom-made testing infrastructure, including targets and the means to produce photographic documentation. On these shooting ranges, the engineers – and sometimes Alfred Krupp or his son Friedrich Alfred in person – received delegations from foreign customers. These were engineers, military attachés or politicians who came to inspect and approve the products before closing the deal. Many of the visits were photographically documented as well, resulting in a four-volume album covering the period up to 1930. Twice, in 1879 and 1882, the company held large technical demonstrations in front of guests, from eighteen and thirteen states respectively, appropriately calling them ‘shootings for the nations’ (Völkerschießen).

The accompanying group photographs with people gathered around and atop immense machinery represent a particular community of states that were highly invested in the global arms race and, in general, played a significant role in world politics and the global economy, similar to contemporary forums, such as the G20. The list of attendees also reflected current diplomatic relations: France, for instance, was not invited to the presentation in 1879. This is a case in point indicating the intricacies of the arms trade, which, despite the industry’s supranational operations, was often bound to political relations between states.

Another prime example are the wars and animosities in South America. During the War of the Pacific (1879–1883), the antagonists, Chile and Peru, tried to buy weapons from British manufacturers through official and less official channels, while at the same time appealing to the government to block their opponent’s orders. Britain finally decided to block all exports to stay neutral in the conflict, which led Chile to turn to France and Germany as allies and business partners. This demonstrates the possibilities and limitations of the arms trade as a tool of control for imperial powers operating in the periphery.[16]

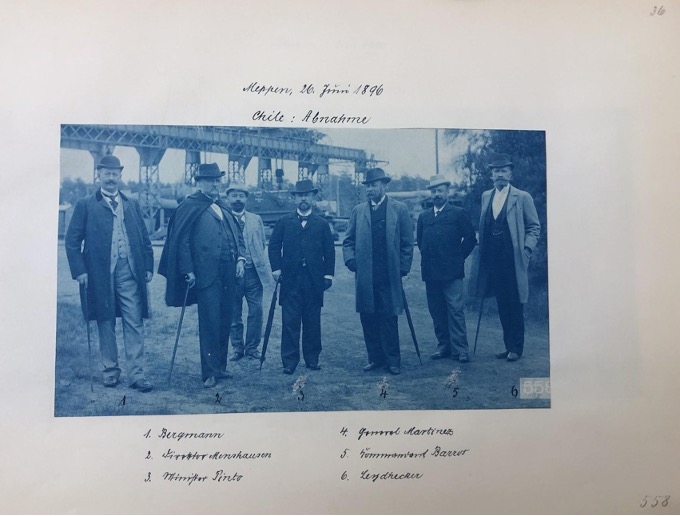

The changing relationships are visible in Krupp’s photographic albums of visits to its shooting ranges by foreign delegations. Chile’s military attachés visited twice in the 1896. Although the Chilean army and navy crushed those of Peru and Bolivia and became a significant power in Latin America, its military expansion continued as the concurrent animosity with Argentina lingered on. Unresolved border disputes and the competition to become the pre-eminent force in the region led to a spiralling arms race between the two nations that lasted until the early 1900s. Argentina, too, visited Krupp’s shooting ranges, and it appears that they did so even more often than Chile, with fourteen images between 1893 and 1906 found in the albums (making it the most frequent guest after Japan).

The conflict provided Krupp with lucrative deals, yet the company did not look on passively and wait for state representatives to knock on its door. To run the global business, Krupp had a network of offices and agents in significant capitals. They were in charge of maintaining personal relationships with clients and promoting new machinery. It might be possible that the photographs of the foreign delegations, which come with the names of the visitors and their rank, constituted a valuable directory of the people in charge – and, importantly, a record of their likenesses – for the company’s agents. The communication kept in Krupp’s archive shows that they not only received news from the headquarters in Essen but also collected information from their local milieu and sent it back to Germany. To coordinate and expand the stream of information, the company established its own intelligence office in 1890. The office was fed with general data on countries, current political debates and developments and, of course, the local arms industry. Moreover, the agents tracked the arms deals of foreign firms and governments: this information was gathered in Essen and redistributed to agents in other countries.[17] Possessing up-to-date and independent intelligence was a decisive asset for Krupp since negotiations were often influenced by the purchasing plans of competing states.

However, it was not only information about other companies that proved valuable; discretely sharing its own customers’ data was as an equally important part of the sales strategy. The pitting of opponents against one another is well documented in the case of Chile and Argentina. The key protagonist is the diplomat and businessman Albert Schinzinger, whom Friedrich Alfred Krupp met in 1886 on a leisure trip to Egypt and hired as an external agent for South America, where he received handsome commissions for successful sales. In the years around 1890, Schinzinger alternated between meetings with Chilean and Argentine representatives, each time notifying the other party about current purchases. Jonathan Grant tracked these movements, finding that ‘Schinzinger, having sold more Krupp guns to Chile in 1892, moved on to Buenos Aires and sold Argentina six batteries of Krupp field guns.… Schinzinger then told the German ambassador, Gutschmid, to alert Chile that “Argentina’s warlike preparations were directed against Chile”’.[18] Besides convincing these countries to buy ever more weapons, this strategy also paid off in terms of gaining market share from competitors. Both the Chilean and the Argentine navy mostly bought from the British manufacturer Armstrong, but when Argentina gradually started buying more weapons from Krupp, Chile followed suit and also replaced their Armstrong guns with Krupp guns.[19] Although bribery was unsurprisingly also part of the game, no party wanted to be behind in purchases or the latest technology in this military display of power.[20] The arms race was thus not only a competition of relative firepower but also had a qualitative aspect to it: it was a matter of prestige.[21] What weapons one had and the company they came from were of equal importance, precisely because this reflected access to certain networks and resources that hinged on diplomatic relations, as Chile learned in the war of 1879.

Therefore, the presence of representatives at the Krupp shooting ranges was highly symbolic. The photographs were not publicised, being fed instead into the company’s archive, but neither were the individual deals, which nevertheless made the rounds for the reasons outlined above. Posing with new military equipment produced by a leading manufacturer boosted the egos of these men, who massively indebted their countries in a bid to become more powerful than their peers. In the same vein, the photographs were also testimony to Krupp’s worldwide success. This becomes clear from the fact that not all inspections led to purchases (which, just like successful deals, was duly noted next to the photographs), yet the pictures were still incorporated in the albums. Having the world at the Krupp shooting ranges was a source of pride, especially when the delegations included high-ranking statesmen, such as the Chinese general Li Hongzhang in 1896 or Argentina’s former President Julio Roca in 1906.

4. From Back Rooms to Postcards

The arms race between Chile and Argentina put their navies among the eight most powerful in the world, behind the United Kingdom, France, Russia, the United States, Italy, Germany and Japan – that is, the great colonial powers. According to Pablo Lacoste, their ships per capita ratio even surpassed that of these much larger states, with Chile leading the statistics. While absolute numbers still showed that the British fleet was ten times larger, the French five times, and the US three times, the military clout amassed in the Southern Cone was such that a shift in alliances could decisively change the global power balance.[22] Luckily for the local population, the conflict did not end in war but was settled through a large-scale scientific effort to determine the border in Patagonia. Nevertheless, the scale of the arms race was enormous and, building on Chile’s and Argentina’s preceding war campaigns against indigenous communities, furthered the process of military history becoming synonymous with national history and prestige.

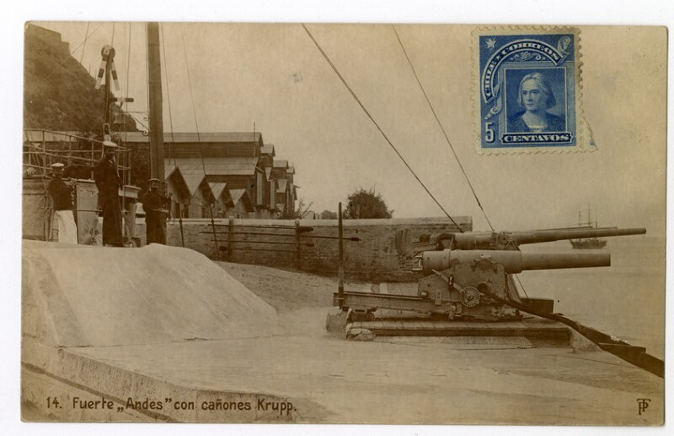

Monuments to war heroes, street names inspired by ships and postcards of battle sites left their mark on the public space. Again, Krupp was also present in this much more visible discursive ground. A postcard of the Fort ‘Andes’ protecting the harbour of Valparaíso shows Krupp cannons overlooking the sea.

It was mailed to a certain María Jofré in the same city, suggesting that the fort and its artillery were a symbol of local pride. It was distributed by Eggers & Cía., a company specialising in typical Chilean mountain scenery, railways, and flores chilenas, photo collages of beautiful women. Within this repertoire, the military post and its German weapons became part of the national imagery.

This was a double success for Krupp: on the one hand, the company influenced the bellicose atmosphere between Chile and Argentina in the back rooms of diplomacy, while, on the other, its reputation steadily rose in the public sphere. Guns and postcards both sold to the satisfaction of the company, the one fostered by the social capital built up by Krupp, the other becoming a currency in itself.

[1] ‘Nur nicht sparsam mit der Zahl der Exemplare … denn das ist eine gute Saat.’ Alfred Krupp in a letter to the Krupp Corporation, 10 July 1875. Quoted in Barbara Wolbring: Krupp und die Öffentlichkeit im 19. Jahrhundert: Selbstdarstellung, öffentliche Wahrnehmung und gesellschaftliche Kommunikation, Munich: C.H.Beck (2000) (Schriftenreihe zur Zeitschrift für Unternehmensgeschichte 6), p. 136.

[2] Bodo von Dewitz: ‘“Die Bilder sind nicht teuer und ich werde Quantitäten davon machen lassen!” Zur Entstehungsgeschichte der Graphischen Anstalt’, in Klaus Tenfelde (ed.): Bilder von Krupp: Fotografie und Geschichte im Industriezeitalter, Munich: C.H.Beck (1994), pp. 40–66, p. 43.

[3] Quoted in Bodo von Dewitz: ‘“Die Bilder sind nicht teuer und ich werde Quantitäten davon machen lassen!” Zur Entstehungsgeschichte der Graphischen Anstalt’, in Klaus Tenfelde (ed.): Bilder von Krupp: Fotografie und Geschichte im Industriezeitalter, Munich: C.H.Beck (1994), pp. 40–66, p. 55.

[4] Bodo von Dewitz: ‘“Die Bilder sind nicht teuer und ich werde Quantitäten davon machen lassen!” Zur Entstehungsgeschichte der Graphischen Anstalt’, in Klaus Tenfelde (ed.): Bilder von Krupp: Fotografie und Geschichte im Industriezeitalter, Munich: C.H.Beck (1994), pp. 40–66, p. 41.

[5] ‘Ich wünsche daher dieses Photographieren aller Arbeiter für immer einzuführen und eine viel strengere Kontrolle über die Leute, ihre Vergangenheit, ihr Treiben und Leben. Wir müssen selbst unsere Privatpolizei haben, die besser instruiert ist als die Städtische.’ Krupp, writing from Torquay on 30 December 1871, as quoted in Bodo von Dewitz: ‘“Die Bilder sind nicht teuer und ich werde Quantitäten davon machen lassen!” Zur Entstehungsgeschichte der Graphischen Anstalt’, in Klaus Tenfelde (ed.): Bilder von Krupp: Fotografie und Geschichte im Industriezeitalter, Munich: C.H.Beck (1994), pp. 40–66, p. 42.

[6] ‘… auf einige Tausend Thaler Mehrkosten kommt es gar nicht an.’ Rudolf Herz: ‘Gesammelte Fotografien und fotografierte Erinnerungen: Eine Geschichte des Fotoalbums an Beispielen aus dem Krupp-Archiv’, in Klaus Tenfelde (ed.): Bilder von Krupp: Fotografie und Geschichte Im Industriezeitalter, Munich: C.H.Beck (1994), pp. 240–267, p. 255.

[7] Rudolf Herz: ‘Gesammelte Fotografien und fotografierte Erinnerungen: Eine Geschichte des Fotoalbums an Beispielen aus dem Krupp-Archiv’, in Klaus Tenfelde (ed.): Bilder von Krupp: Fotografie und Geschichte Im Industriezeitalter, Munich: C.H.Beck (1994), pp. 240–267, p. 254. Krupp had been considering the psychological effect of advertising since the early 1870s.

[8] Rudolf Herz: ‘Gesammelte Fotografien und fotografierte Erinnerungen: Eine Geschichte des Fotoalbums an Beispielen aus dem Krupp-Archiv’, in Klaus Tenfelde (ed.): Bilder von Krupp: Fotografie und Geschichte Im Industriezeitalter, Munich: C.H.Beck (1994), pp. 240–267, p. 255.

[9] Rudolf Herz: ‘Gesammelte Fotografien und fotografierte Erinnerungen: Eine Geschichte des Fotoalbums an Beispielen aus dem Krupp-Archiv’, in Klaus Tenfelde (ed.): Bilder von Krupp: Fotografie und Geschichte Im Industriezeitalter, Munich: C.H.Beck (1994), pp. 240–267, p. 255.

[10] Rudolf Herz: ‘Gesammelte Fotografien und fotografierte Erinnerungen: Eine Geschichte des Fotoalbums an Beispielen aus dem Krupp-Archiv’, in Klaus Tenfelde (ed.): Bilder von Krupp: Fotografie und Geschichte Im Industriezeitalter, Munich: C.H.Beck (1994), pp. 240–267, p. 263.

[11] Barbara Wolbring: Krupp und die Öffentlichkeit im 19. Jahrhundert: Selbstdarstellung, öffentliche Wahrnehmung und gesellschaftliche Kommunikation, Munich: C.H.Beck (2000) (Schriftenreihe zur Zeitschrift für Unternehmensgeschichte 6), p. 231.

[12] Bodo von Dewitz: ‘“Die Bilder sind nicht teuer und ich werde Quantitäten davon machen lassen!” Zur Entstehungsgeschichte der Graphischen Anstalt’, in Klaus Tenfelde (ed.): Bilder von Krupp: Fotografie und Geschichte im Industriezeitalter, Munich: C.H.Beck (1994), pp. 40–66, p. 59.

[13] Bodo von Dewitz: ‘“Die Bilder sind nicht teuer und ich werde Quantitäten davon machen lassen!” Zur Entstehungsgeschichte der Graphischen Anstalt’, in Klaus Tenfelde (ed.): Bilder von Krupp: Fotografie und Geschichte im Industriezeitalter, Munich: C.H.Beck (1994), pp. 40–66, p. 42.

[14] Bodo von Dewitz: ‘“Die Bilder sind nicht teuer und ich werde Quantitäten davon machen lassen!” Zur Entstehungsgeschichte der Graphischen Anstalt’, in Klaus Tenfelde (ed.): Bilder von Krupp: Fotografie und Geschichte im Industriezeitalter, Munich: C.H.Beck (1994), pp. 40–66, p. 50.

[15] Jonathan A. Grant: Rulers, Guns, and Money: The Global Arms Trade in the Age of Imperialism, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (2022), p. 6.

[16] Jonathan A. Grant: Rulers, Guns, and Money: The Global Arms Trade in the Age of Imperialism, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (2022), p. 121.

[17] Barbara Wolbring: Krupp und die Öffentlichkeit im 19. Jahrhundert: Selbstdarstellung, öffentliche Wahrnehmung und gesellschaftliche Kommunikation, Munich: C.H. Beck (2000) (Schriftenreihe zur Zeitschrift für Unternehmensgeschichte 6), p. 230.

[18] Jonathan A. Grant: Rulers, Guns, and Money: The Global Arms Trade in the Age of Imperialism, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (2022), p. 130.

[19] Jonathan A. Grant: Rulers, Guns, and Money: The Global Arms Trade in the Age of Imperialism, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (2022), p. 130.

[20] See Jonathan A. Grant: Rulers, Guns, and Money: The Global Arms Trade in the Age of Imperialism, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (2022), p. 125; George v. Rauch: Conflict in the Southern Cone: The Argentine Military and the Boundary Dispute with Chile, 1870–1902, Westport, CT: Praeger (1999), p. 129n80.

[21] Jonathan A. Grant: Rulers, Guns, and Money: The Global Arms Trade in the Age of Imperialism, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (2022), p. 116.

[22] Pablo Alberto Lacoste: ‘Chile y Argentina al borde de la guerra 1881–1902’, in: Anuario del Centro de Estudios Históricos 1/11 (2001), pp. 301–328, pp. 317–318.