TalkPhotogenics

Armin Linke, Estelle Blaschke, Peter Szendy

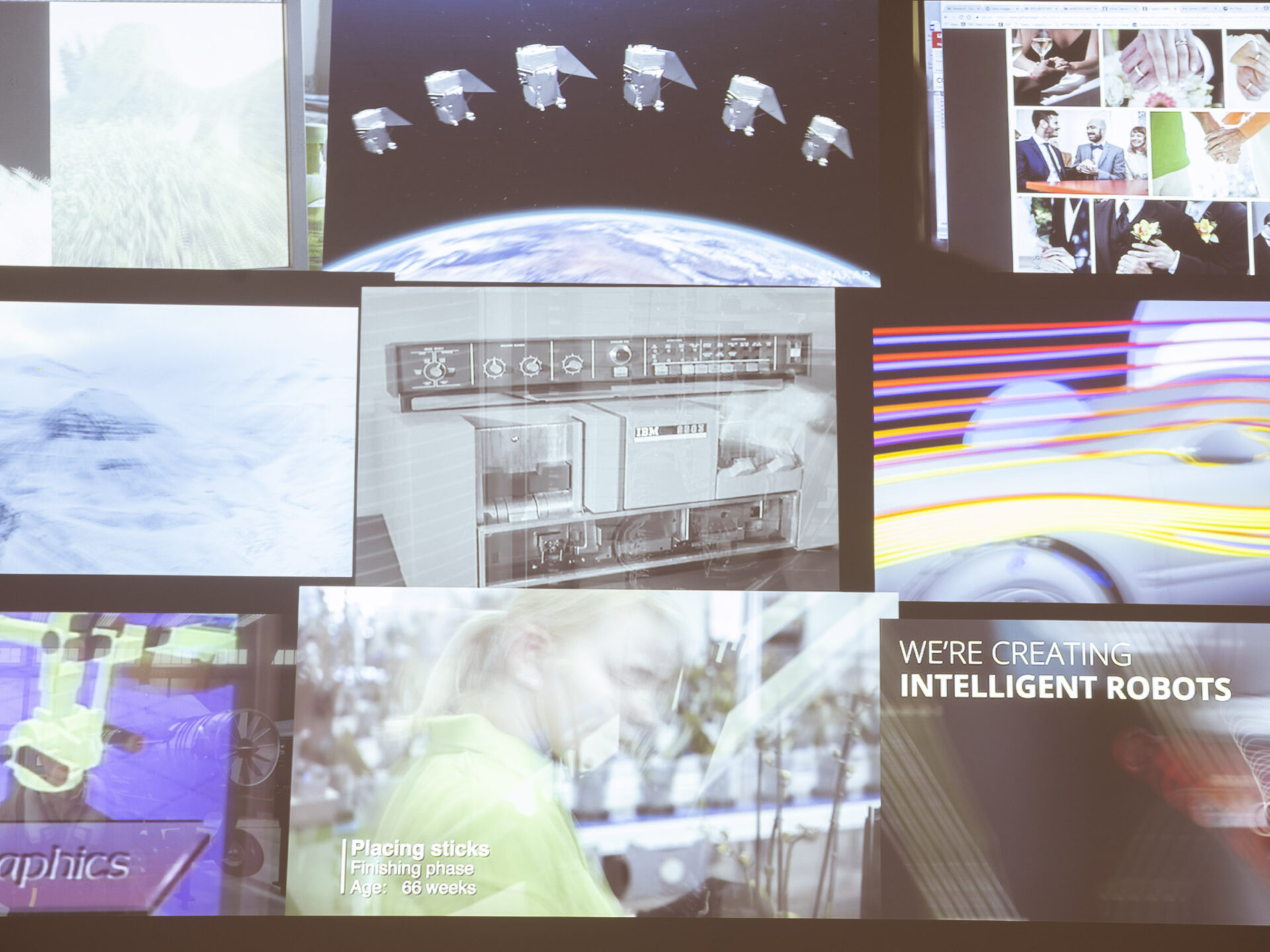

Photogenics

Capital Image – Photogenics. In the series of: “Parole aux expositions Capital Image“. © Centre Pompidou, Paris, 10.11.2023.

Capital Image – Photogenics. In the series of: “Parole aux expositions Capital Image“. © Centre Pompidou, Paris, 10.11.2023.

Capital Image – Iconomies de l’ombre et algorithmisation des images. Ce que le capitalisme numérique fait au visible. In the series of: “Parole aux expositions Capital Image“. © Centre Pompidou, Paris, 16.02.2024.

Capital Image – New Open Image: Architecture et culture visuelle dans l’âge de l’IA générative.

In the series of: “Parole aux expositions Capital Image“. © Centre Pompidou, Paris, 08.02.2024.

Capital Image – Iconomies de l’ombre et algorithmisation des images. Ce que le capitalisme numérique fait au visible.

In the series of: “Parole aux expositions Capital Image“. © Centre Pompidou, Paris, 16.02.2024.

Capital Image – Photogenics.

In the series of: “Parole aux expositions Capital Image“. © Centre Pompidou, Paris, 10.11.2023.